Florence laGanke Harris

Florence laGanke Harris

2022 Inductee

In 1928, Florence LaGanke Harris published the first of the “Nancy Page” syndicated columns. Unlike her fellow columnists such as Laura Wheeler and Alice Brooks, her columns ran with her own name as well as her pen name. In the “Nancy Page” columns, she created a fictional world for Nancy and her quilting group. Each week a new pattern was provided, and progress cited on the previous week’s block. Her columns included block patterns, recommended color choices, quilting designs, and finishing techniques – and if a quilter became impatient for the next column, it was possible to send a self-addressed, stamped envelope to her local newspaper and receive the complete instructions for the quilt.

By 1928 when the syndicated column began, Florence LaGanke Harris was already an accomplished author, editor, wife, and community leader. Florence, born on May 2, 1886, was one of 5 children born to her German immigrant father, Robert, and her Cleveland, Ohio native mother, Lillie. Her older brother, Wilbur, was born in 1884; her sister Ruth in 1891; Nelson in 1899 and youngest brother Leland in 1904.

Florence attended Pratt Institute in New York and later received a B.S. in Education at Columbia University. Her first job was as a dietitian at St. Luke’s Hospital in Cleveland (1910-1912). The job resulted from serving a steak to the Rev. Ward Pickard, superintendent of St. Luke’s Hospital, who hired her on the spot!

From 1913 to 1918, she was an instructor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. In 1919, Florence moved to California to become the Superintendent of Home Economics in Oakland, Ca. She later returned to Cleveland in 1923 to become the Home Economics Editor of the Cleveland Plain Dealer and to write a daily column on the “art of homemaking.” The Cleveland Plain Dealer introduced Florence with her photo and the following words:

Equality of the sexes may be a fine thing, but already women are getting tired of it! Letters written by young women in California, Nova Scotia, Florida, and Maine come to Florence LaGanke with the same refrain, ‘What do we care about the liberation of the feminine sex? What we want are happy homes.’ Their letters show that the trend is definitely turning back to the domesticity of their grandmother’s day.

Florence married Frederick Ashton Harris on November 3, 1923, in Cleveland. She was 37 years old. The couple had no children and Florence kept her maiden name throughout her professional career.

In 1928, Florence’s syndicated columns began and continued for 17 years until 1945. These columns were tremendously popular and could be found in at least 400 metropolitan newspapers. They were recognized as the most popular Sunday feature with 32% of the women reading them.

As Nancy Page, Florence published 27 series quilts in total, as well as single block patterns (many of which were sent in by readers). The earliest in 1928 and 1929 was “Grandmother’s Garden Quilt.” This series was copyrighted by Publishers Syndicate as a weekly series appearing in such newspapers as the Nashville Banner, Indianapolis Star, Dayton Daily News, Buffalo Times, and the Lowell Sun. The copyright ended in 1956 and 1957 and passed into the public domain. The pattern was reproduced by Eleanor Burns in 1999.

The “Alphabet Quilt” was published for 25 weeks in 1929-1930. Twenty-four blocks were included ending with the distinctive diagonal “Y O U” (or the child’s name substituted). “X” and “Z” were not included. By 1936, the pattern was offered in kit form by Mary McElwain of Wadsworth, Wisconsin.

“Garden Bouquet” ran from February through July of 1932. Each week, a flower pattern in an urn with a pair of charming birds was printed (20 urn blocks – each with a different flower). In describing this new quilt, Florence wrote: “The quilt I have designed this time ought to please those of you who like flowers. I think it will please those who like birds. I hope it will please all of you who like to sew and to make the kind of appliqué that grandmother did.” She also referenced cutting out the patterns and adding them to their “Nancy Page Scrapbook.” By 1932, 10 cents was being charged for any missed pattern

Other series in the “Nancy Page Quilt Club” included: “The Magic Vine” (reproduced by Eleanor Burns in 2007), “Old Almanac Quilt,” and “French Bouquet Quilt” (originally published by Publishers Syndicate as a weekly series in newspapers in 1933 and reproduced by Quilters Newsletter Magazine in 1991).

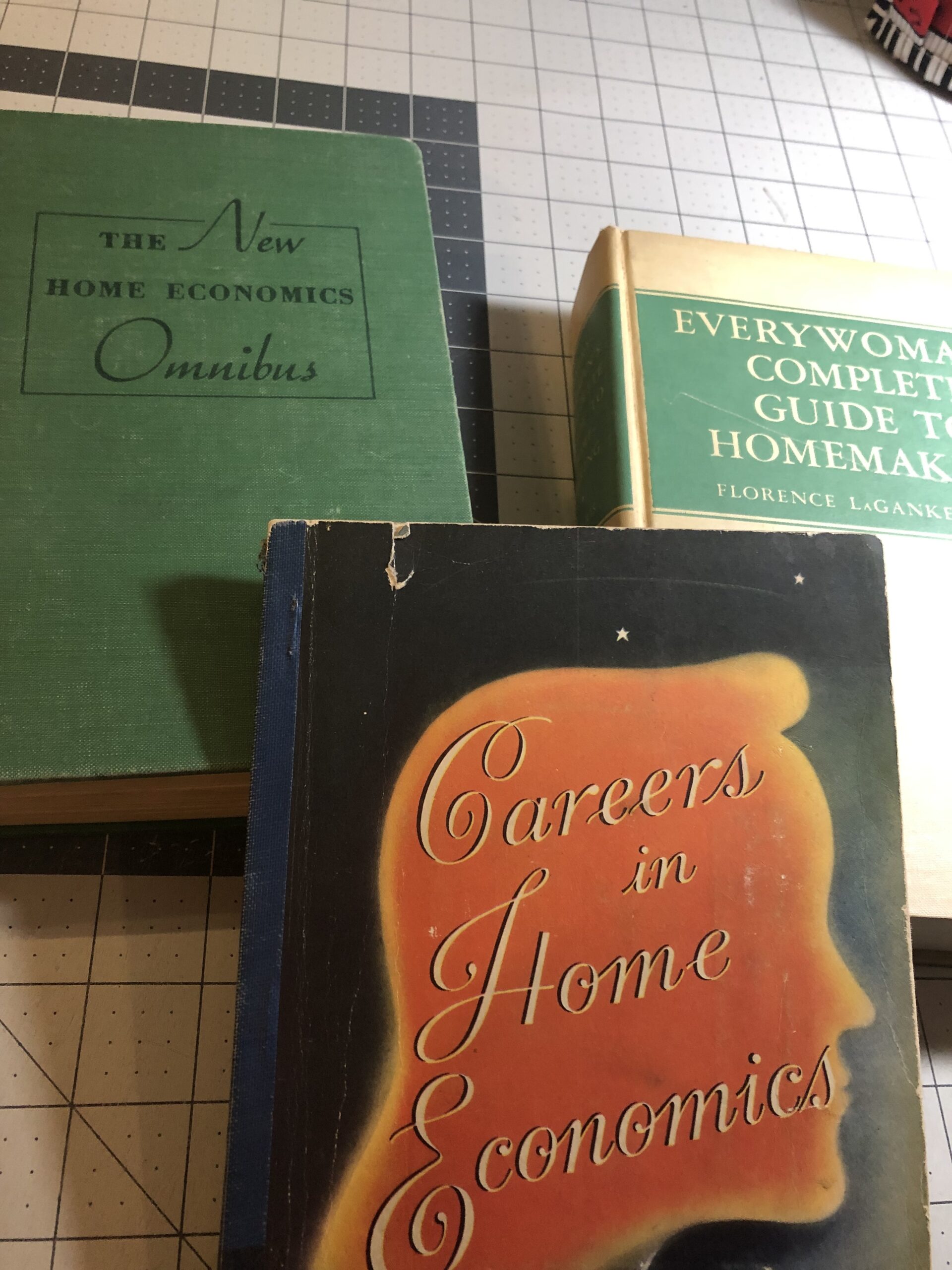

From 1930 until her retirement in 1967, Florence served as food editor of The Cleveland Press. Known as the “dean of the nation’s food writers,” she authored at least 15 cookbook titles including: Everywoman’s Complete Guide to Homemaking, Victory Vitamin Cookbook for Wartime Meals, and 400 Salads. Florence spoke about the word “gourmet”: “What does it mean? To me it means a baked Maine potato with freshly ground salt, pepper, and butter or sour cream. ‘Gourmet’ means good food, plainly but well prepared, and served with a flare with occasional foreign overtones.”

In the Introduction to Everywoman’s Complete Guide to Homemaking, Florence writes:

This book is being started in a cabin in the Maine woods, where life is reduced to the simplest elements. The cabin is furnished with a cot, a table, a chair. There is a shelf that holds a wash basin, a pail, and a dipper. Bathing is done in the lake. My clothes are the simplest possible. The small mirror hanging on the back of the door discourages any urge to cosmetics. The bedtime candle does not lead me to consider reading myself to sleep.

The bare idea of a need for a homemaker’s guide, a handbook for her help, seems absurd. Why bother with baking temperatures, or correct length for draperies, or the accepted placement of silver, or the modern folding of napkins? After a few days’ stay here, the futility of much of our squirrel-cage living is so plain that I keep wondering why I ever grow ‘hot and bothered’ over little things. I watch the shadow of the leaves as the sunlight filters through. I see the reflection of the fleecy clouds in the placid lake. I say to myself, ‘What a dumb idea book writing really is!’ And then one of the camp directors comes to me and says, ‘Just what is the best way to get soot off the bottom of the campfire kettles?’ or, ‘Do you know how we can put away camp blankets, so the red squirrels won’t nibble them next winter?’ And I decide that even the simplest living presents questions that demand answers.

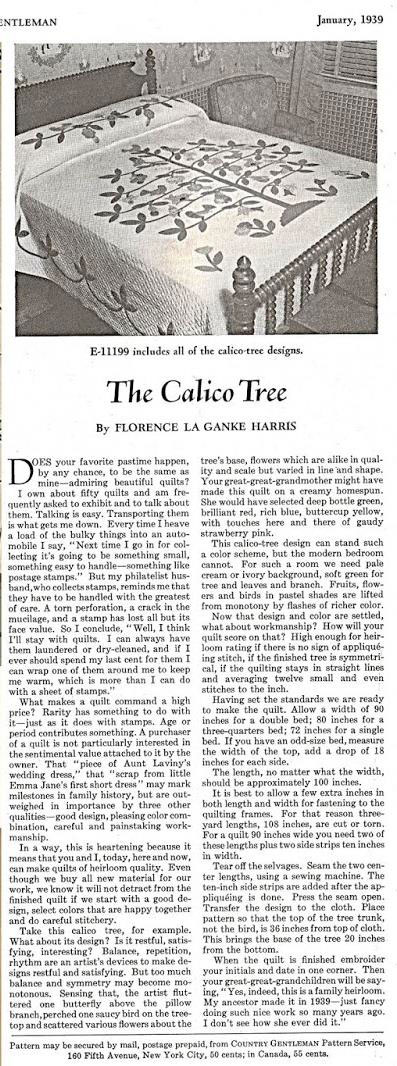

Florence frequently made public appearances, judged quilt contests, and spoke about her antique quilt collection, offering her accumulated wisdom on quilt design:

- The design of a quilt should be restful, balanced, consistent, and rhythmic.

- Colors used today are softer than those used by our ancestors. They needed warmth in their quilt colors to counteract the bare whitewashed walls and uncovered stained floors. We need pastels to combine happily with fine woods, dainty hangings, wallpaper, and carpets.

- Fine quiltmaking requires that meticulous care be employed in cutting and piecing.

- Quilting stitches must be fine, twelve to an inch; the lines must be straight, close together; there must be no visible sign of the marking which guided the quilting.

- Any quilt worthy of being an heirloom should have the initials or name of the maker and the date of making worked at one end or in one corner.

Florence died on March 1, 1972 in Cleveland, OH at 85 years of age. She had spent more than half a century advising Cleveland, the nation, and the world on the art of homemaking. Once described as about as “big as a minute,” Florence was a woman of great energy who let few things interfere with her work. She returned to her column in only 10 days after breaking her hip and judged a baking contest in NY with a broken arm. She bequeathed over 3,000 cookbooks, texts, pamphlets, and periodicals to the Cleveland Public Library upon her death in 1972.

As Florence wrote in Everywoman’s Complete Guide to Homemaking:

The revived interest in quilt-making has led to a greater appreciation of the quilts which have been handed down from generation to generation. Some of these are indifferently made and have been cherished largely because of the sentiment attached to them. But those worthy of the name ‘heirloom quilts’ possess beauty of design, harmonious color arrangement, and exquisite stitchery.

Thanks to Florence and designers like her, the high standard of quilt making continues!

By Amy Korn

“Any quilt worthy of being an heirloom should have the initials or name of the maker and the date of making worked at one end or in one corner.”

Florence LaGanke Harris

Everywoman’s Complete Guide to Homemaking

Selected Reading

Alboum, Rose Lea. The Nancy Page Index of Quilt Designs. West Halifax: self published, 2005.

Brackman, Barbara. “Who Was Nancy Page?” Quilters Newsletter Magazine. September 1991: 22-29+.

Brackman, Barbara. Women of Design: Quilts in the Newspaper 1928-1961. Kansas City: The Kansas City Star Books, 2004.

Burns, Eleanor. The Magic Vine. San Marcos: Quilt in a Day, Inc., 2007.

Burns, Eleanor and Patricia Knoechel. Grandmother’s Garden Quilt. San Marcos: Quilt in a Day, Inc., 1999.

Harris, Florence LaGanke. Careers in Home Economics. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1942.

Harris, Florence LaGanke. Everywoman’s Complete Guide to Homemaking. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1936.

Harris, Florence LaGanke and Hazel H. Huston. The New Home Economics Omnibus. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1942.

Kaisand, Heidi, editor. “1930-1939: A New Deal with Quilts.” Better Homes and Gardens Century of Quilts. 2002: 44-62.

Kiracofe, Roderick. The American Quilt: A History of Cloth and Comfort 1750-1950. New York: Clarkson Potter, 1993.

Waldvogel, Merikay. Soft Covers for Hard Times: Quiltmaking and the Great Depression. Nashville: Rutledge Hill Press, 1990.

Waldvogel, Merikay. “Quilt Design Explosion of the Great Depression.” On the Cutting Edge: Textile Collectors, Collections, and Traditions. Ed. Jeannette Lasansky. Lewisburg: Oral Traditions Project, 1994.

Who’s Who of American Women. Second edition, 1961-1962. Wilmette, IL: Marquis Who’s Who, 1961.

Woodward, Thomas K. and Blanche Greenstein. Twentieth Century Quilts 1900-1950. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1988.