Patsy Orlofsky and Textile Conservation

I have a small follow-up before I get to this week’s Honoree. You may remember that when I wrote about Honoree Cuesta Benberry, I invited those who knew her to share information. There’s only so much you can learn from the internet, and I hoped to take advantage of personal knowledge while it’s still available. (Quilt historians take note; we should be doing more of this across the board.) Well, to my pleasant surprise, I received a communication from Quilters Hall of Fame founder, Hazel Carter.

Hazel gave me some information about Cuesta’s “Always There” quilt. She related that Cuesta was adamant that she did not make the blocks herself. I knew that Cuesta wasn’t much of a quiltmaker, but I knew she had participated in round robins, and I thought she made at least some of those blocks. (There’s a link below where you can see a number of blocks from Cuesta’s collection that now belong to the Quilters Hall of Fame.) Hazel was able to tell me that Bettina Havig, who published a book of Honoree Carrie Hall’s 800 block patterns, had done one, as had a friend of Bettina’s. Hazel thought the makers’ names might be recorded as part of the documentation at the University of Michigan, but I can’t find it. Can anyone else help? If you made a block, or know who did, please share your knowledge.

I was saving this for later, but now is as good a time as any to tell you that Hazel Carter created a block to honor Cuesta Benberry. Here’s a shot of Cuesta’s induction to TQHF with the block on the wall behind her and Hazel, and the pattern–in case you’re ambitious.

Okay, now we can get to Honoree Patsy Orlofsky. If you know her name, it’s probably because you own or have come across the book she wrote with her husband Myron called Quilts in America. Published in the Bicentennial era (is that, or will it become a recognized “era”?), this coffee table book was intended to raise the status of quilts as collectible antiques or objects of folklore.

Google Books describes it as follows:

This work on traditional quilts offers guidelines for establishing the age of antique quilts and information on the areas of the country where they were made. Techniques, tools, fabrics and dyes are described in detail, along with all the known types and patterns of quilt and how to care for them.

In writing the book, Patsy brought her art history background and experience as a crafts teacher, but both she and Myron came to it with an interest in authentic American folklore objects. You can read more about Patsy’s life at the bio link below. What interests me is their idea that even worn out, faded quilts were worth inclusion in the book; not being in pristine condition showed what they called “the life of the quilt.” This viewpoint is reminiscent of the Velveteen Rabbit: “ ‘Real isn’t how you are made,’ said the Skin Horse. ‘It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real’.”

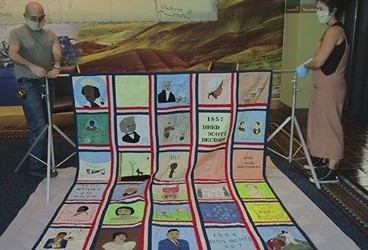

But it’s a viewpoint that perhaps runs contrary to Orlofsky’s other claim to fame. After writing Quilts in America, Patsy turned her talents to textile conservation and in 1977-8 she established the Textile Conservation Workshop (TCW) in South Salem, New York where she still works as Executive Director. TWC is a not-for-profit organization that treats textiles of historic importance and artistic value, serves as a consultant to cultural institutions around the country, and maintains an active outreach education and survey program for small museums and historical societies. Here’s an example of a recent project.

TWC will restore this quilt, which was damaged in a riot in the area of the Oregon Historical Society. The front will be repaired and the backing replaced. OHS will retain the backing as a separate object to document the history of the quilt and the riot.

Being on the TQHF Collections Committee, the work that Orlofsky and TWC do for museums is especially important to me. But you only need to be aware of quilting’s historical significance to appreciate their work. We wouldn’t have such wonderful museum exhibits (and lately, virtual viewings) if conservators like Orlofsky weren’t at work behind the scenes. If you are interested in a general overview of conservation and curator functions, you will find Orlofsky’s “Textile Conservation” article (link below) to be informative and approachable. Just a small example of TWC’s good work.

Let’s take a look at some of the conservation work TWC does. I’ll share some photos, but there’s also a link below if you want more eye candy. There aren’t many quilt shots on the website, but the before/after section is inspiring, and Eeyore will be a hit. Here’s Patsy Orlofsky, inspecting an object stored (properly) in an acid-free box.

There’s a good bit of science and chemistry involved. Fabrics are identified and tested for color-fastness, and solvents may be used for cleaning. The photo on the left shows the use of a suction table which aids in controlled application of the chemicals.

-

Photo: TWC -

Photo: TWC

Of course, it’s not just historically-significant quilts that need repair and restoration. How many of us have done our best to preserve a family heirloom? Or even an ordinary piece? This morning I noticed a small tear (defective fabric? A slip of the rotary cutter?) in a table topper I was half-way through quilting. It was too late to replace the offending piece, so I hand appliquéd a patch using the leftover fabric. That was easy; I didn’t have to worry about finding matching fabric, dealing with fading or shattering, or preserving authenticity. So, hat’s off to those, like Patsy Orlofsky, who do real conservation.

Your quilting friend,

Anna

Cuesta’s blocks. https://quiltershalloffame.pastperfectonline.com/webobject?utf8=%E2%9C%93&search_criteria=cuesta&searchButton=Search

Bio info. https://quiltershalloffame.net/patsy-orlofsky/

Article. http://www.museumtextiles.com/uploads/7/8/9/0/7890082/orlofsky_textile_conservation.pdf

TWC website. https://www.textileconservationworkshop.org/