Rose Kretsinger and Carrie Hall: Part One

By Deb Geyer

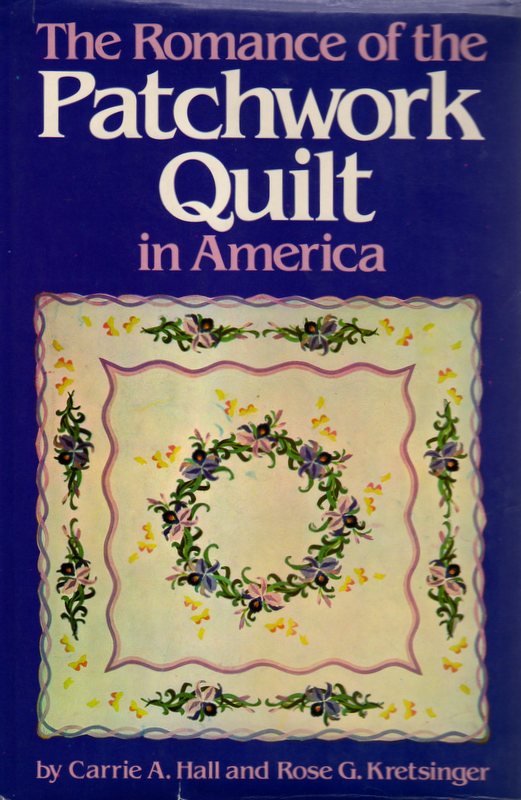

Rose Kretsinger and Carrie Hall are best known for the book they co-authored, The Romance of the Patchwork Quilt in America, published in 1935. Their influences on the world of quilting earned them each the honor of being inducted into The Quilters Hall of Fame in 1985. Carrie Hall had a romantic and poetic manner of describing the history of this American art and Rose had a way of encouraging beauty and order in everyday living.

On the occasions of Rose’s birthday (November 29) and Carrie’s birthday (December 9) I’d like to share with you what I have learned about Rose and Carrie and their influences on the world of quilting. Their stories have taught me much about the world of the early 1900s and have given me a greater appreciation for the Arts and Crafts movement.

Rose Francis Good was born November 29, 1886. Growing

up in Abilene, Kansas, Rose was surrounded by creative people. Her mother

painted china. Her grandfather made pottery and built carriages. Her

grandmother was a quilt maker. An Emporia Gazette article reported Rose as

saying her grandmother taught her to make her first stitches on a quilt, but

she said that she abandoned the craft as soon as the lessons were over. However

disinterested she may have been in quilting, her early years were full of creativity

and adults that encouraged her creativity.

After graduating from high school, Rose went to

Chicago to work on a degree in design at the Art Institute of Chicago. The

program at the Art Institute placed emphasis on the Arts and Crafts movement

which promoted traditional craftsmanship using simple forms based on nature.

Followers of the arts and crafts movement sought to create a style based on

simplicity of design, quality of craftsmanship, attention to detail and

integration of art into everyday life. Rose graduated with honors from this

program. Over the next six years she designed fabric for Marshal Field Department

Store, designed jewelry, taught at the Art Institute, and studied Architecture

in Europe for a year.

At the age of 28, Rose retired from her design career, moved to Emporia, Kansas and married William Kretsinger, a well-to-do widower who was an attorney as well as a rancher. They raised two children, William and Mary Amelia. Rose kept busy adding beauty to their family’s home and the ordinary objects it contained. She did cross stitch, petit point, embroidery, and appliqué. During the Colonial Revival, Rose took up quilting at the age of forty. That year, 1926, Rose made three quilts, Snow Crystals, Democrat Rose, and Antique Rose. While they were all based on traditional patterns, Rose’s artistic skill and professional competence gave the quilts a distinct sophistication.

As she continued her quilting, Rose ignored commercial trends, focusing instead on quilts of the past. The patterns and kits of the day resulted in a predictable product; a quality Rose criticized. “Women are depending more upon the printed pattern sheet to save time and labor. These, having been used time and again, often become very tiresome.” Rather than buying her patterns from magazines, she found most of her ideas in old quilts, borrowing family heirlooms from friends and sketching museum quilts. Her quilts honor the accomplishments of those who came before her and are evidence that her philosophy to study the work of others was practically applied to her own work.

The success of Rose’s quilts lies in her reworking of

the old designs. With her design background she knew how to reorganize compositions

to focus attention, how to use color and value, and how to use quilting to add

line. Rose’s unique combination of traditional standards and modern design

earned her local and national fame as she won prizes in contests from Lyon

County, Kansas to New York City. Rose did all the hand appliqué work on her

quilts. She designed and laid out the quilting but hired others to do the hand quilting.

Rose would occasionally accept payment for quilt designs, but she did not have a business. Her daughter Mary said, “All she did was for the joy of doing it. She had unlimited energies for passing patterns and help around to other quilters.”

For her part in The Romance of The American Quilt, Rose wrote Part III, “Quilting and Quilting Designs”. Rose dedicated this section to her mother, Anna Gleissner Good. This section includes a short history of quilting and goes into detail on quilting designs. She expressed discontent with the commercialization of quilting in her day, which she felt lowered its sincerity and individuality as a needle art. Rose promotes quilting as valuable for the display of individual taste and self-expression.

“It has been said by different disinterested people: ‘Why spend so much time and labor making new quilts and worrying about designs when you already have a number which are never used?’ Perhaps it is for the same reason which prompts the planting of flowers in the alley, back of the garden fence, or the landscaping of our gardens in places seen only by a few; because of our love for beauty and regard for order in everyday living. It is in us and must come forth and become a material artistic expression.”

Rose suffered a paralyzing stroke sometime before her death in 1963. During the 15 years before her death, Rose had spread Paradise Garden, the last quilt she finished, on her bed only on special occasions. But when she was confined to bed after her stroke, she asked her daughter Mary to put it over her. The quilt was needed to bring her joy. Rose had written, “We are always well repaid in making something lovely, for ‘A thing of beauty is a joy forever.'” Rose died June 23, 1963 in Wichita, Kansas, at the age of 76.

In 1971 her daughter donated twelve quilts made by Rose to the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas.

Selected Quilts: Click on the quilt titles to see photos on the Spencer Museum of Art website.

Indiana Wreath, 1927- This quilt was inspired by a quilt used for the frontispiece of the early editions of Marie Webster’s book, Quilts: Their Story and How to Make Them, published in 1915. Made by Elizabeth J. Hart, the original Indiana Wreath quilt has inspired many excellent quilters to create their own interpretations of the challenging design.

Orchid Wreath, 1928- Rose’s daughter, Mary, said she saw a Coca Cola poster with orchids on it in a local soda fountain. She asked her mother to make an orchid quilt for her bed. Rose asked for the poster and used it as a design source for the quilt. This is the only quilt that Rose made with an original design and was included in the exhibit America’s 100 Best Quilts of the 20th Century at the International Quilt Festival in 1999.

Paradise Garden, 1946- Rose designed and appliqued this masterpiece, inspired by a quilt made in 1857 by Arsinoe Kelsey Bowen, which was illustrated in Ruth Finley’s book, Old Patchwork Quilts and the Women Who Made Them. This was Rose’s last quilt.

Selected Reading:

Brackman, Barbara. “Rose Kretsinger.” The Quilters Hall of Fame: 42 Masters. Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press, 2011.

Brackman, Barbara, Jennie A Chinn, Gayle R Davis, Terry Thompson, Sara Reimer Farley, Nancy Hornback. Kansas Quilts & Quilters. Lawrence, Kansas, University of Kansas Press, 1993.

Carter, Hazel. “Evolution and New Revelation: The Garden Quilt Design.” Blanket Statements, American Quilt Study Group, no. 71 (Winter 2003).

Gregory, Jonathan. “The Joy of Beauty: The Creative Life and Quilts of Rose Kretsinger.” Uncoverings, American Quilt Study Group, Vol 28 (2007).

Hall, Carrie A., and Rose G. Kretsinger. The Romance of the Patchwork

Quilt in America. Caldwell, ID: The Caxton Printers, Ltd., 1935.

Leman, Bonnie. “Two Masters: Kretsinger & Stenge.” Quilter’s

Newsletter Magazine, no. 128 (January 1981).

“Rose Kretsinger, Appliqué Artist.” Quilter’s Newsletter

Magazine, no. 97 (December 1977) (Interview with daughter Mary Kretsinger

of Emporia, Kansas.).

Shankel, Carol, ed. American Quilt Renaissance: Three Women Who

Influenced Quiltmaking in the Early 20th Century. Tokyo: Kokusai Art,

1997.