Rose Kretsinger and Carrie Hall: Part Two

By Deb Geyer

Rose Kretsinger and Carrie Hall are best known for the book they co-authored, The Romance of the Patchwork Quilt in America, published in 1935. Their influences on the world of quilting earned them each the honor of being inducted into The Quilters Hall of Fame in 1985. Carrie Hall had a romantic and poetic manner of describing the history of this American art and Rose had a way of encouraging beauty and order in everyday living.

On the occasions of Rose’s birthday (November 29) and Carrie’s birthday (December 9) I’d like to share with you what I have learned about Rose and Carrie and their influences on the world of quilting. Their stories have taught me much about the world of the early 1900s and have given me a greater appreciation for the Arts and Crafts movement.

Carrie Hall

She was born Carrie Alma Hacket in Caledonia, Wisconsin on December 9, 1866. Apparently, Carrie declared that she was born with a needle in her hand. Although I could not find any solid evidence to support that, Carrie seems to have spent most of her life with a needle in her hand. Her father, a soldier in the Union Army during the Civil War fostered a love of Abraham Lincoln in Carrie. Her mother nurtured a love of books and fashion. In 1874, her family moved to a pioneer homestead in Smith County, Kansas. Despite hardships and poverty, books and quilts were considered necessities in their home. At age 7, Carrie pieced a Le Moyne Star Quilt which won first prize at the county fair. A few years later, her excellent needlework won her a subscription to Godey’s Lady’s Book, the fashion bible of the time. Carrie had no high school or college degree but her love of books and studying paid off as she was hired to teach school and was a county school superintendent for a time.

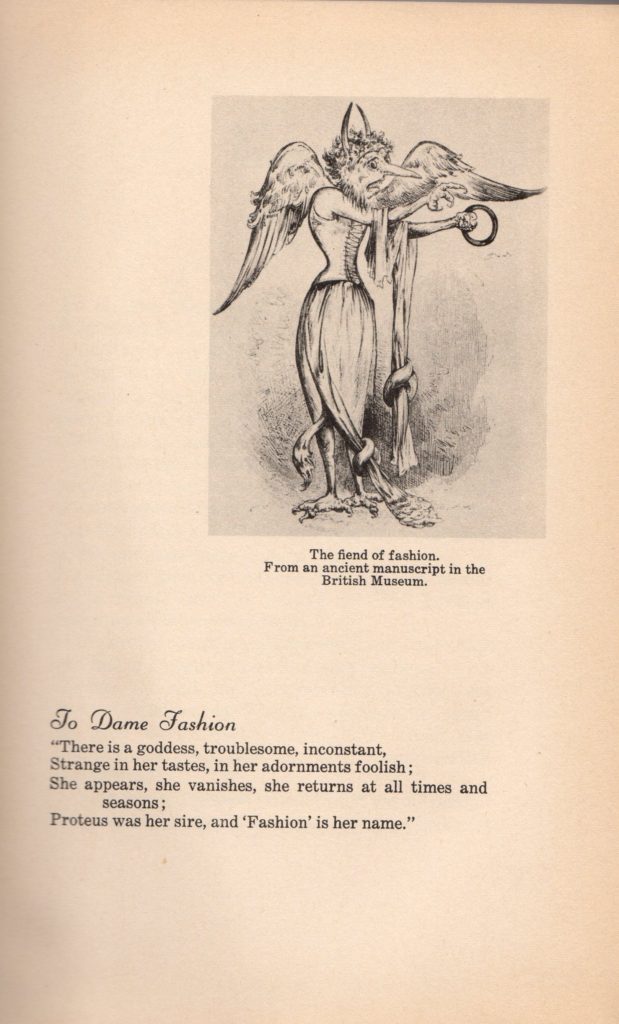

In 1889, when she was 23 years old, Carrie moved to Leavenworth, Kansas and launched a dressmaking business. Carrie had some very strong ideas about clothing and fashion which she shared in her book, From Hoopskirts to Nudity. She felt that clothes influence those who wear them, for good or for evil. She pointed out that fashion illustrations were ill proportioned and unbalanced “and the poor misguided women look at (the illustrations) and try to make themselves into their image.”

Carrie states in her book, “Style and fashion are not synonymous terms although they are so used, indiscriminately and incorrectly. Style, in its relation to dress, is the indescribable something that is so easily recognized and so hard to define. Style is of the person and not of the clothes, for two women may wear a dress of the same design and fabric and one will look like a fashion plate and the other will look like a frump. One will be a ‘vision’ and the other a ‘sight.'”

She felt that fashions were created one size fits all and the poor victims are squeezed or stretched to fit the prevailing mode. “On the other hand, style, like beauty, is eternal and its essential qualities never change throughout the ages, and the woman who possesses this distinction will impose it upon every garment she wears.”

Carrie’s dressmaking business prospered. Known in the business world as “Madame Hall,” she employed many assistants. Her income supported a large home, two ailing husbands (successively), and it supported her habit of collecting books and memorabilia on Abraham Lincoln, Shakespeare and fashion.

After the end of World War I, Carrie began to make quilts. As the quilt revival of the 1920s grew, Carrie had made sixteen quilts. Realizing she could never make a quilt in every pattern, she began to make a sample block of every known quilt pattern at the time. The project grew until she had created well over 800 blocks. She collected even more patterns than she sewed. In the late 1920s the availability of ready-made clothing and the beginning of the Great Depression, caused her dressmaking business to decline. It was at that point Carrie began a career as a quilt lecturer. Dressed in a colonial costume, she presented programs about quilt blocks, quilt making and quilt history, all illustrated with her extensive block collection. She became a prominent club woman, quilt authority, lecturer and quilt collector.

April 10, 1932, Carrie visited Rose Kretsinger at her home in Emporia. She had an idea of a book she wanted to write and she wanted to ask Rose for pictures of quilts for the book. However, a week later Carrie wrote a letter to Rose, in which Carrie describes her vision of a three-volume set of books of which Rose would write the last. Carrie proposed to share one-third of the royalties with Rose and Carrie would handle all the business matters.

A single book was published three years later, in September of 1935. Carrie wrote the first two parts and Rose wrote the final part. Carrie dedicated her parts to “Quilt Lovers- Everywhere: World Without End.” Carrie’s first part covers the history of quilts peppered generously with poetry and prose, showing quilts in a romantic light. She writes about the romance of quilts, the quilting bee, the quilt’s place in art, and how to make quilts. Photos of the quilt blocks Carrie had made are numbered and named. This made the book the first comprehensive index to quilt patterns, their names and their history. In Section Two, Carrie provides photos of completed quilts- antique and modern. Twelve of the quilt photos are from Rose Kretsinger’s collection, made either by Rose or by her mother (To read more about Rose’s contributions to the book, see Part I).

World War II found Carrie dealing with serious financial difficulties. To address shortages in money she turned all of her property over to her creditors, with the exception of her library. With the money raised she was able to care for Mr. Hall who was in poor health and to begin a new life for herself. She began to manufacture and sell playtime and character dolls of historical figures, she prided herself on the detail and craftsmanship of the dolls. She ran this business under the name “The Handicraft Shop” and was quite successful.

At the age of 88, on July 8, 1955, Carrie Hall’s needle was stilled forever. I wonder if she died with a needle in her hand.

Selected Quilts: Click on the quilt titles to see photos on the Spencer Museum of Art website.

George Washington Bi-Centennial Quilt– 1932. Made in Leavenworth, Kansas, the label on this quilt reads: “This quilt is an adaptation of a design by Mary Evangeline Walker. George Washington Bi-Centennial Quilt—the center is a framed silhouette surrounded by two rows of hatchets. The row of cherry trees next and the outer row next represents Washington Pavement. Made by Mrs. Carrie A. Hall, Maplehurst, Leavenworth Kansas. For sale—Price $59.00.”

Cross Patch Quilt– c.1928-1935. This design was developed by Hall from a crossword puzzle.

Selected Reading

Brackman, Barbara. “Madame Carrie Hall.” Quilters Newsletter Magazine, no. 133 (June 1981).

Brackman, Barbara. “Carrie Hall: Entrepreneur.” Women’s Work: Quilts, Making a Living Making Quilts (blog). Womensworkquilt.blogspot.com, March 11, 2018.

Brackman, Barbara, Jennie A Chinn, Gayle R Davis, Terry Thompson, Sara Reimer Farley, Nancy Hornback. Kansas Quilts & Quilters. Lawrence, Kansas, University of Kansas Press, 1993.

Hall, Carrie. From Hoopskirts to Nudity: A Review of the Follies and Foibles of Fashion, 1866-1936. Caldwell, ID: The Caxton Printers, Ltd.

Hall, Carrie A., and Rose G . Kretsinger. The Romance of the Patchwork Quilt in America. Caldwell, ID: The Caxton Printers, Ltd., 1935.

Hammill, Diane. “Carrie Hall.” The Quilters Hall of Fame: 42 Masters. Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press, 2011.

Havig, Bettina. Carrie Hall Blocks: Over 800 Historical Patterns from the Collections of the Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas. Paducah, KY: American Quilter’s Society, 1999.