Rose Kretsinger

Rose Kretsinger

1985 Inductee

Rose Francis Good was born in the small town of Hope, Kansas, on November 29, 1886, and lived most of her adult life in the larger town of Emporia, Kansas. Rose’s father was a partner in Good & Eisenhower, a Hope dry goods store. Shortly before Rose’s birth, Milton Good sold his share to David Eisenhower, and when the new baby was a few weeks old, Rose’s family returned to Abilene. David Eisenhower, who could not make the Hope store profitable, moved two years later to Texas, where he and his wife added a son, Dwight David, a future president of the United States, to their family.

When Rose was in her teens, the family moved again, to Kansas City, Missouri. Rose went to Chicago, were she received a degree in design from the Art Institute of Chicago in 1908. After spending a year studying in Europe, she returned to Chicago, where she designed jewelry during her twenties.

In 1914, Rose Good retired from professional design and moved to Emporia, Kansas, when she married a well-to-do widower, William Kretsinger, who was an attorney and rancher in his early forties. They raised two children, William and Mary Amelia. Rose became an important figure in the clubs and committees that formed the world of the women in her set.

Emporia considered itself more than a mere cow town or railroad junction. It was the “Athens of Kansas,” a nickname bestowed by William Allen White, Emporia’s resident sage. White created a national image of his hometown as the small town, the antitheses of urban, industrial new York City. The town became a national symbol of front porch, main Street values. White liked to describe the town as egalitarian, but there was an upper class for whom he edited his newspaper- “the best people of the city,” he called them.

In 1926, during the Colonial Revival, Rose took up quilting at the age of forty. She had inherited an antique bed and decided to follow the magazines’ advice to cover it with a copy of an authentic old quilt. Quiltmaking was also a form of therapy at first. She found handwork consoling after losing her mother in an automobile accident. Because her friends made such a fuss over her quilt, she entered it in a fair, where, to her surprise, she won the blue ribbon. Pleased with the success of her first effort, she began a second, and over the next two decades produced a remarkable group of quilts.

For her inspiration, Rose ignored commercial trends, focusing instead on quilts of the past. The patterns and kits of the day resulted in a predictable product, a quality Rose criticized. “Women are depending more upon the printed pattern sheet to save time and labor. These having been used time and again often become very tiresome.” Rather than buying her patterns from magazines, she found most of her ideas in old quilts, borrowing family heirlooms from friends and sketching museum quilts. Instead of using the new multicolored dress prints, she preferred nostalgic calicoes and antique fabrics to give the old-fashioned look she wanted.

The extraordinary success of Rose’s quilts lies in her reworking of the old designs. With her design background, she knew how to add drama with vivid colors and black accents, to add line with an overlay of quilting and a scalloped edge, and to add sophistication by reorganizing compositions, tightening up a wandering vine here and filling in a blank space there. She finished her works of art with bold borders. Rose’s unique combination of traditional standards and modern design earned her local and national fame, as she won prizes in contests from the Lyon County Fair to New York City.

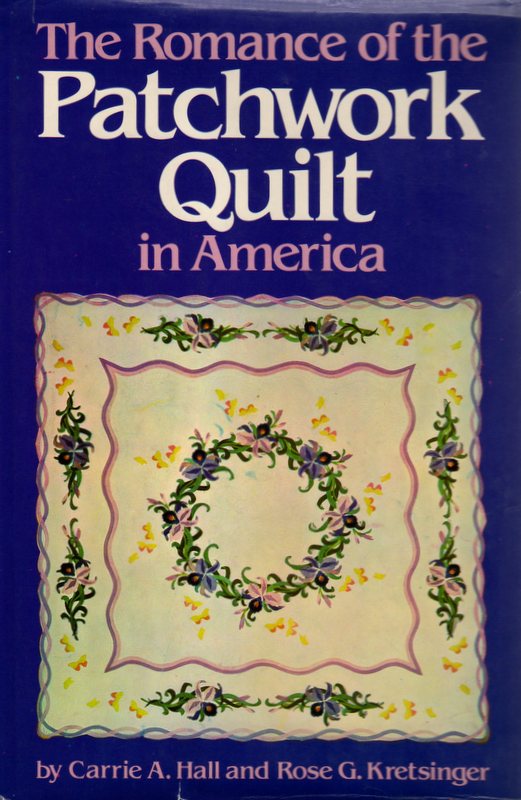

The Kansas City Art Institute mounted an exhibit of her quilts in the early 1930s, and her national reputation grew with the publication in 1935 of the book she coauthored with Carrie Hall, The Romance of the Patchwork Quilt in America. Rose’s contribution was the section on the history of quilting, with photographs and diagrams of antique and contemporary designs.

The Orchid Wreath, made in 1929, is her only truly original design. When her daughter, Mary asked for an orchid quilt to match her bedroom décor, Rose found inspiration in an advertising card she had seen at a soda fountain. her other quilts, antique or commercial patterns redrawn, proved to be showstoppers in the national quilt shows of the 1930s and 1940s.

In the 1942 National Needlework Contest sponsored by Woman’s Day magazine, her quilt Calendula won a second prize. The first prize was won by Piné Hawkes Eisfeller of Schenectedy, New York for her variation of the heirloom medallion wreath quilt called The Garden, made in 1857 by Arsinoe Kelsey Bowen and published in Ruth Finley’s Old Patchwork Quilts and the Women Who Made Them. Second prize must have vexed Rose, for she wrote the terse criticism “Poor Design” under the magazine photo of Eisfeller’s prizewinning Cottage Garden. Rose then designed her own version, which she finished in 1946 and called Paradise Garden, the quilt many consider to be her masterpiece. The quilt and her orchid Wreath were selected by a panel of experts for the exhibit America’s 100 Best Quilts of the 20th Century at the International Quilt Festival in 1999.

Emporia was an unusual place, where quiltmakers developed a community aesthetic with high standards for design, craftsmanship, and originality. Rose often displayed her quilts in contests and exhibits, inspiring others to attempt their own designs or to request her patterns. She communicated her design ideas and craftsmanship by example, sharing patterns and assisting other quiltmakers. With her talent, training, generosity, and competitive nature, she was at the heart of Emporia’s exceptional quiltmaking community.

Rose did not do the quilting on her work. Many women before World War II hired professional quilters, a traditional division of labor. The Kretsinger children remember their mother sending her tops out to be quilted, although the quilters’ names have been forgotten. It also seems apparent that Rose designed her own quilting patterns and worked closely with the quilters.

Rose appliquéd most of her quilts between 1926 and 1932. In 1940, she was widowed at the age of fifty-four, when William Kretsinger died of heart failure. She began her last quilt, Paradise Garden, shortly after his death. Rose died in Emporia in 1963 at the age of seventy-six.

In 1949, Farm Journal magazine sold two of her designs, Oriental Poppy and Old Spice, the only full-size patterns she published. In 1971, her daughter, Mary Kretsinger, donated twelve quilts made by Rose and two made by Rose’s mother to the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas. Rose Kretsinger was inducted into The Quilters Hall of Fame in 1985, with her coauthor, Carrie Hall.

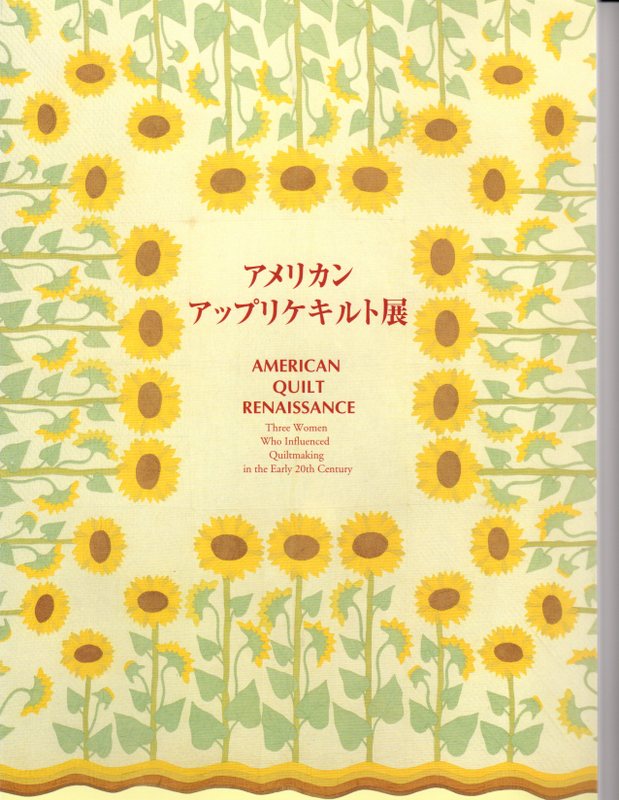

Rose Kretsinger’s quilts continue to inspire quiltmakers to the present day. In 1992, the Wichita Art Museum and the Kansas Quilt Project organized the exhibit Midcentury Masterpieces: Quilts in Emporia, Kansas, which featured the appliqué work of Rose Kretsinger and her Emporia friends. In 1998, her quilts toured Japan and were featured in the publication American Quilt Renaissance: Three Women Who Influenced Quiltmaking in the Early 20th Century, along with the work of honorees Carrie Hall and Marie Webster.

By Barbara Brackman

“Beautiful things appeal to the emotions and create a sort of mental state of quiet and spiritual goodness… We might even liken the quilt to musical composition. It has its high and low color tones, and its swelling and diminishing line rhythm; all carrying the eye through a design composition.”

Rose G. Kretsinger, The Romance of the Patchwork Quilt in America (1935), pp. 261-262

The Romance of the Patchwork Quilt in America, the book Rose coauthored with Carrie Hall, features a photo of Orchid Wreath on the cover.

![]()

Photo courtesy of the Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, gift of Mary Kretsinger

American Quilt Renaissance: Three Women Who Influenced Quiltmaking in the Early Twentieth Century featured the work of TQHF honorees Rose Kretsinger, Carrie Hall, and Marie Webster. The catalog was published in 1997 and served as the catalogue for an exhibition organized by the Indianapolis Museum of Art and the Spencer museum of Art, which traveled to Japan.

Photo courtesy of Mary Kretsinger and Barbara Brackman

Selected Reading

Carter, Hazel. “Evolution and New Revelation: The Garden Quilt Design.” Blanket Statements, American Quilt Study Group, no. 71 (Winter 2003).

Hall, Carrie A., and Rose G. Kretsinger. The Romance of the Patchwork Quilt in America. Caldwell, ID: The Caxton Printers, Ltd., 1935.

Leman, Bonnie. “Two Masters: Kretsinger & Stenge.” Quilter’s Newsletter Magazine, no. 128 (January 1981).

“Rose Kretsinger, Appliqué Artist.” Quilter’s Newsletter Magazine, no. 97 (December 1977) (Interview with daughter Mary Kretsinger of Emporia, Kansas.).

Shankel, Carol, ed. American Quilt Renaissance: Three Women Who Influenced Quiltmaking in the Early 20th Century. Tokyo: Kokusai Art, 1997.