Ruth Finley: Old Patchwork Quilts

Last week I wrote about the 50th Anniversary of the Whitney Museum Abstract Art quilt exhibit. Little did I know that I would find (or create in my own mind) a link between the quilts in that exhibit and today’s honoree, Ruth E. Finley.

You may-and if you’re a quilt historian, you should- know Ruth Finley as the author of the second comprehensive book on US quilt history. (The first, of course, being Marie Webster’s Quilts: Their Story and How to Make Them.) You can read some basic bio information about Ruth at the link below.

In 1929, Finley published Old Patchwork Quilts and the Women Who Made Them. She traced the development of quilting from Colonial times, often in a romanticized way, and included stories from her family and other quilters to demonstrate her points. Some of her history has been debunked, as noted in these quotes from the International Quilt Museum website:

Essentially, the “scrap bag” myth goes like this: colonial women needed something to keep their family warm, so they recycled scraps of fabric into bedcoverings, creating a utilitarian object from otherwise useless bits and pieces. During this time progressive-thinking Americans applied Darwin’s theory of evolution to anything and everything, including quilts. In Old Patchwork Quilts (1929), Ruth Finley speculated that quilts evolved from chaos into order, with necessity-driven scrap quilts serving as the first step. Finley did not base her theory on existing quilts; she and other early 20th-century quilt enthusiasts assumed that because examples of such colonial-era scrap quilts did not exist, they had been used up.

Research in women’s diaries and household inventories has shown that women shared textile work. Work parties of the period included barn raisings, harvestings, and huskings in addition to quilt parties. Ruth Finley romanticized quilting bees. The myth transitioned the focus of quilting parties from work-centric to social. The myth turned the quilting bee into a match-making party, an opportunity for young men and women to meet in acceptable social settings after having spent the day working.

OK; so there is a good bit of speculation, extrapolation and even fabrication in Finley’s book. But, as Barbara Brackman notes in her Introduction to the third edition of Old Patchwork Quilts, at the time she was writing, Finley didn’t have access to all the academic writing we have today—she only had one book as a guide (Marie Webster’s book published in 1915).

Old Patchwork Quilts included an attempt to record patterns and names, to describe fabrics, dyes, and quilting techniques, and to put all of this in an historical context. History was important to Finley; the whole family seems to share this interest and they maintain family artifacts and letters dating to the late 1700s. The house Finley grew up in is still in the distaff side, passed to a descendant of her sister, Mary.

You can read more about Finley’s Colonial Connecticut connections and how she incorporated family legends into Old Patchwork Quilts at the link below to an article by Ricky Clark.

Finley concluded her tome with the sad observation that while women had advanced socially and economically since Colonial days, they did so at the expense of the handiwork into which they had poured their hearts, and that quiltmaking was a dying art.

Boy! Was she wrong on that last count! And she may have recognized, by the time she finished the 16 years of research and writing that went into the book, that the tide was turning back. Here’s what she said in her foreward:

My purpose in writing this book has been twofold: First, to make a record, with the hope that it might prove definitive, of one of the most picturesque of all American folk arts; secondly, to interpret that art in relation to the life of the times during which it most widely flourished. This purpose was itself prompted by the lately renewed interest in patchwork, both old and new–an interest enthusiastically active at the moment and rapidly growing.

Maybe Old Patchwork Quilts even contributed to the revival of quilting in the 1930s and 40s.

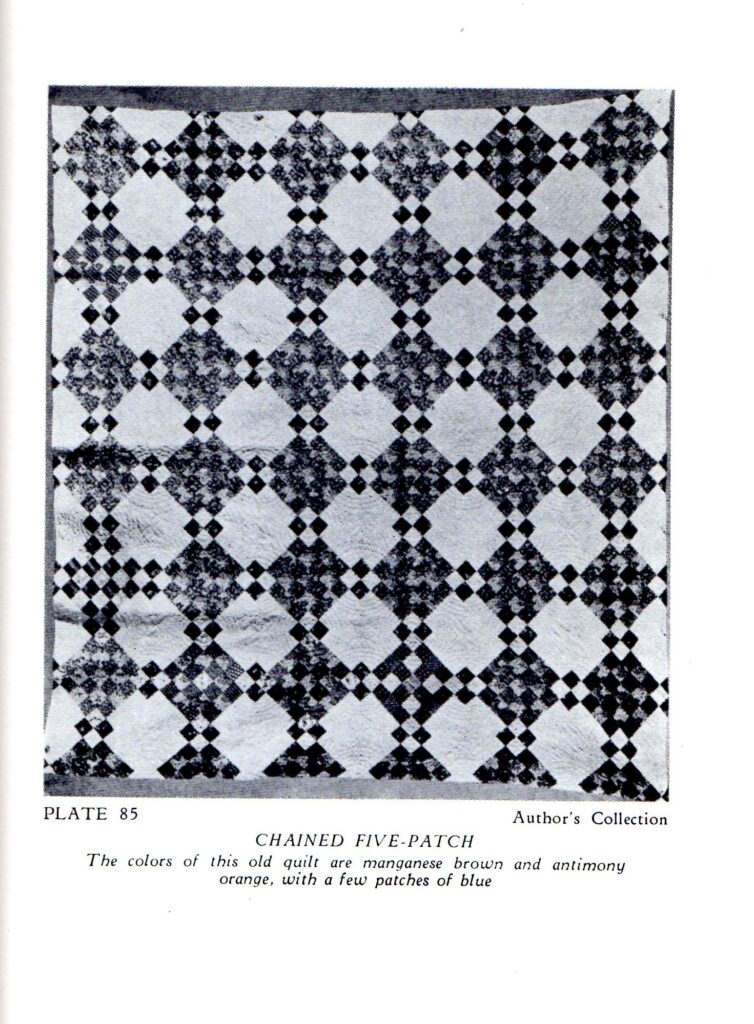

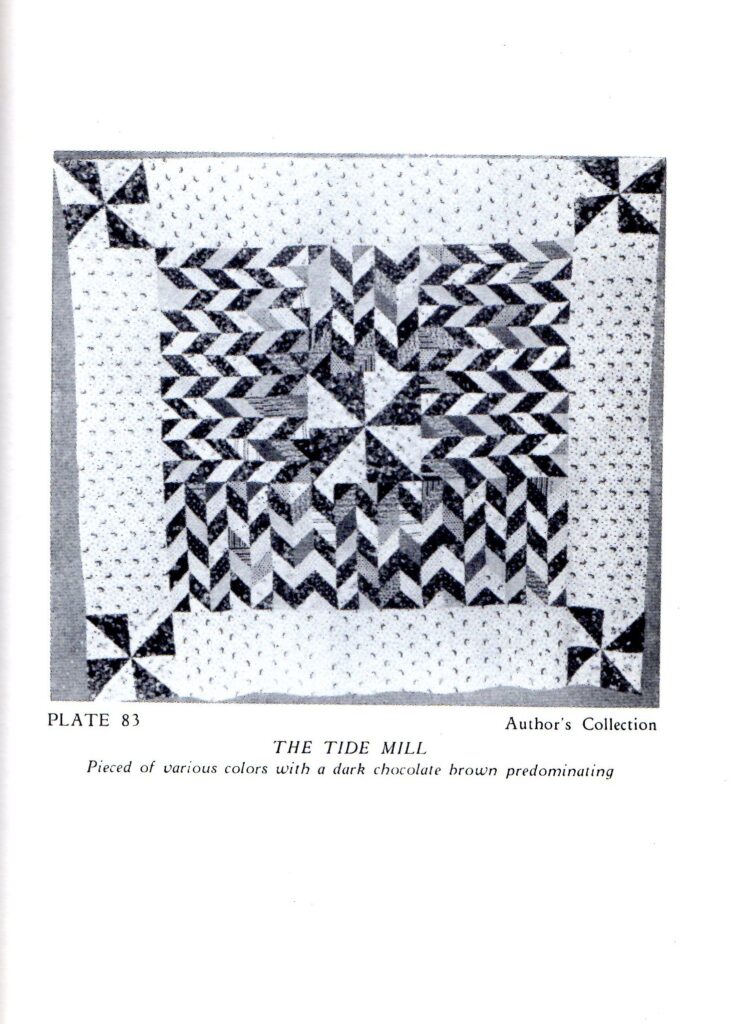

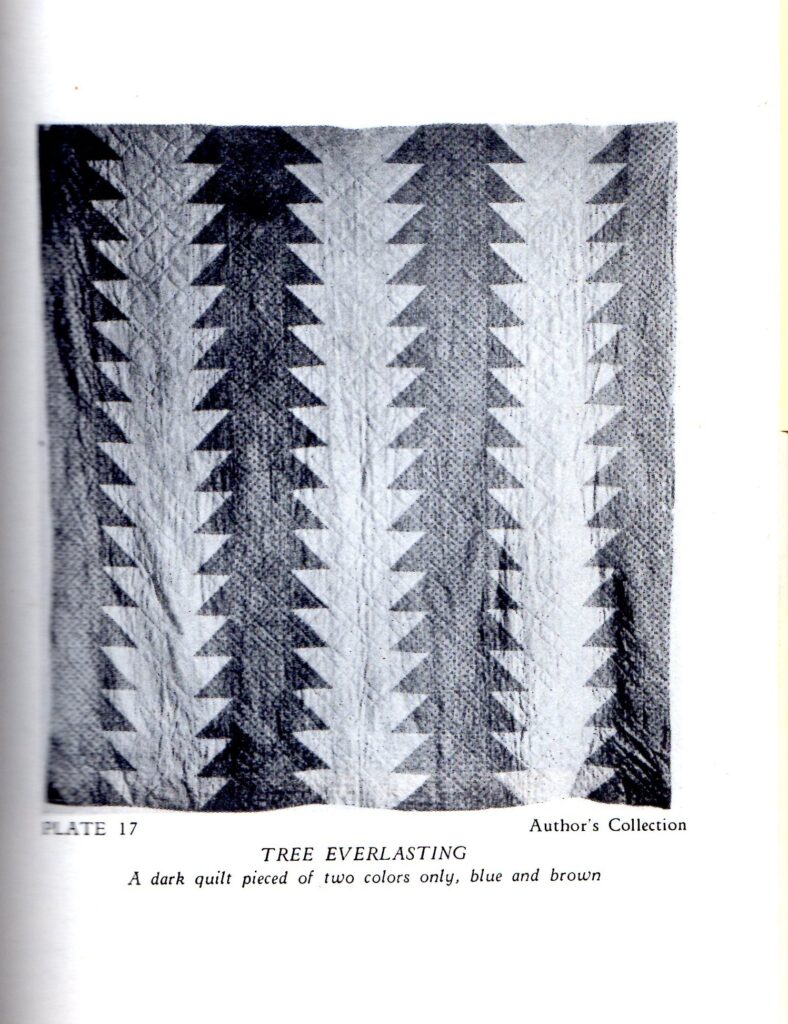

So you ask, what’s the connection to the Whitney exhibit? Graphics; quilts as art. Finley herself collected quilts, and many of the plates in her book are from her own collection. In this sample of photos taken from Old Patchwork Quilt you can see the powerful lines of abstract art.

And Finley herself almost predicted the theme of the Whitney exhibit. She wrote,

“Incidentally, this pattern (Hosanna) particularly emphasizes the fact that most quilts are, as one would say today, futuristic—in both color and form. More than one old quilt, like the “Indian Hatchet’, ’Tree Everlasting’, and …. are prophetic of the latest trend in domestic design as to be quite startling. Or would it be heresy to suggest that modernistic art is reminiscent of folk-crafts the creations of which have gone so completely out of memory as to seem now strikingly novel?”

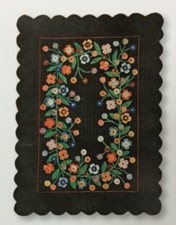

Finley’s collection also included appliqué and non-geometric quilts. One of the most famous to pass through her hands was this one:

She also designed a quilt, “The Roosevelt Rose”. Finley, although considered a feminist and supporter of women’s labor and education reform, is said to have been a life-long Republican although her parents were Democrats and hosted McKinley in their home, where Ruth presented him with a small bouquet and a little speech. Who knows? Concerning the quilt, she told reporters that it was the first quilt pattern named for a President since Lincoln. (What about Garfield’s Monument? A piece of Ohio history she should have been familiar with.) She also mused that the 19th century fashion of naming blocks for historical events hadn’t produced a 20th century block named “Fourteen Points for Peace”. Here’s “The Roosevelt Rose”.

Quilt Pattern” as published in Good

Housekeeping, January, 1934

When Old Patchwork Quilts came out, it was publicized all over the country. Finley’s husband, Emmett, who headed the Associated Press wire service, was probably responsible for such wide-spread coverage. The promos were especially popular when they could be treated with “poetic license” to fit an editor’s needs, as seen in these two opportunistic articles. Finley herself never associated “Pine Tree” with Christmas, and she described the second quilt as a bride’s quilt named “Lotus Flower.” But the holiday connections sold newspapers.

Ah! Newspapers! As important as we think Old Patchwork Quilts may be, that wasn’t what got Ruth Finley into Who’s Who in America; her career in journalism did that. She started at the Akron Beacon Journal where, notably, she scored an interview with the former Akronite wife of Thomas Edison and earned her first by-line by interviewing Mrs. Henry Ford. Her career took off when she moved to the Cleveland Press and did a series of articles on the condition of working women. These articles were syndicated and published throughout the US.

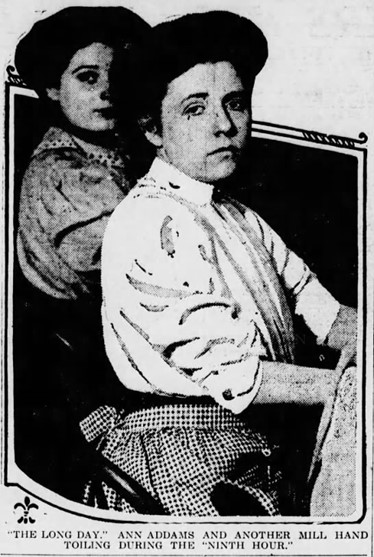

Following in the tradition of the undercover work of Nellie Bly (who stayed 10 days in an asylum for an exposé), and the muckraking tactics of Ida Tarbell, Finley assumed the persona of a working girl, Ann Addams. She worked in a restaurant (a week), laundry, mill, sewing shop, factory; was “insulted in a mansion”. Once again, the editors took liberties and made it seem that “Ann” was on assignment to them; here’s a headline from Wilkes-Barre, PA; similar headlines appeared in Oklahoma, Washington, and Indiana.

And here are the accompanying syndicated photos for “Ann’s” jobs:

In the shop girl story, “Addams” exposes the issue of piece work, favoritism, and unwanted advances.

In this article, pretty little Emily, sick from food poisoning through a meal that was part of her wages, is “holding her fort like a wounded soldier” until she collapses and is taken out back and left while the other waitresses had to continue to push through the lunch rush.

Here, “Addams” tells about metal cuts on the working girls’ hands and the cost of “prosperity” at the expense of the working girls who are forced to put in extra hours.

“There was a peculiar interest attached to being literally cast into the streets of a strange city, sick, friendless, and with only $2.36 in my pocket by a woman who posed before her clubs as a humanitarian and philanthropist with special concerns of in the welfare of working girls.” In this story, the mistress won’t let “Ann” wear a coat to do front porch work and terminates her when she shows signs of pneumonia (but says she will welcome back such a good worker if she isn’t sick.)

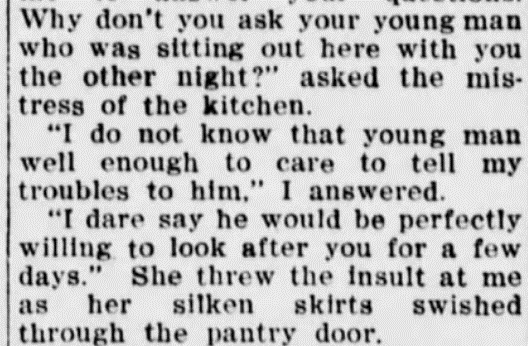

And this is where the “insult” comes in. “Ann” describes in the article how she pleaded with the mistress that she had no place to go. After suggesting she go to the YWCA but refusing to tell “Ann” where it was, the following colloquy ensues:

If it’s true that “Ann” only had one male visitor during her tenure, there may be a little backstory here, as related on Karen Alexander’s blog

“It was while working as a housemaid on an undercover story about working conditions for lower-income women that she met her future husband, also a journalist. Ruth feared her “missus” was getting suspicious because all her previous maids had had a “young man” calling on them and Ruth wanted to distract her from any questioning, so she asked the boss to send someone over. The boss chose Robert Finley, though not without some protest on Finley’s part. Within a few months the serendipitous meeting ended in a marriage with her boss taking credit in print in the newspaper for bringing them together!”

Finley’s journalistic career wasn’t all so sensational. She was woman’s page editor of the Cleveland Press, fiction editor of the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain, managing editor for the old Washington Herald, woman’s editor of the Enterprise Newspaper Association, assistant editor of McClure’s magazine and editor of Guide Magazine and the Woman’s National Political Review. She also wrote about Sarah Josepha Hale, the editor of “Godey’s Ladies Book” (who must have been something of a hero for Finley in her crusading aspect and a role model in her professional one—Finley thought someone should have designed a quilt block named for Hale). And no discussion of Ruth Finley is complete without telling that she and her husband were occultists and wrote under the pen name “Darby and Joan” about their spiritualistic encounters with a World War I soldier. What a varied career!

I hope you enjoyed reading a little about Ruth Finley.

Your quilting friend,

Anna

Bio info. https://quiltershalloffame.net/ruth-finley/

Ricky Clark, “Ruth Finley and the Colonial Revival Era”. https://quiltindex.org/view/?type=page&kid=35-90-191