Ruth Finley

Ruth Finley

1979 Inductee

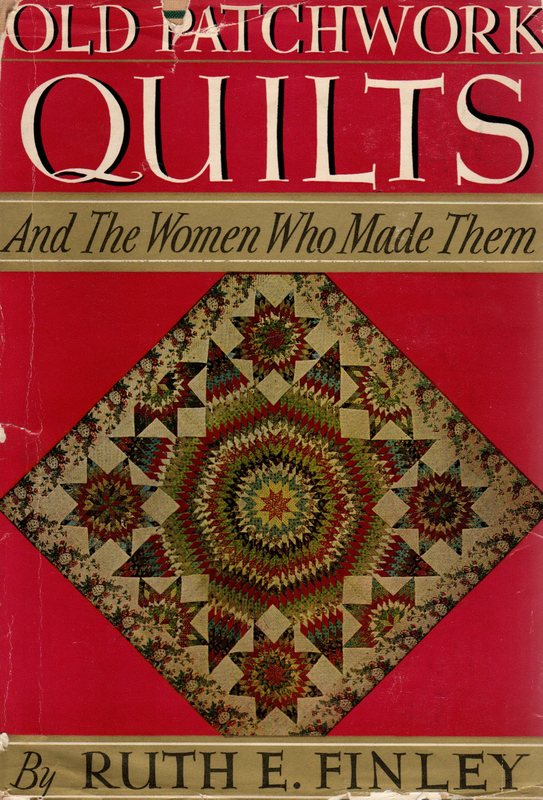

Ruth Finley secured her reputation as a recognized authority in the quilt world with the 1929 publication of her book Old Patchwork Quilts and the Women Who Made Them. To the present day, this work is a popular resource for authors and quilt researchers, due largely to its detailed descriptions and pattern diagrams, along with nearly one hundred photographs of quilts and fabrics. Its folksy narrative style gives it a personal appeal.

Ruth was born September 25, 1884, into the socially prominent and well-educated Ebright family of Akron, Ohio. Her father was Dr. Leonidas S. Ebright, a physician who served at various times as surgeon general of Ohio, a state representative, and Akron’s postmaster. Her mother, Julia Bissell Ebright, was a graduate of Oberlin College, the first American college to grant degrees to women. Julia’s family, with seventeenth-century roots in Connecticut, had two state governors in its lineage.

Ruth used her background advantages as an embarkation point for her own intellectual pursuits and creative undertakings. Lovina May Knight, a family friend of the Ebrights, described Ruth as a young woman who possessed an attractive combination of good health, strength, and femininity, with a perceptive wit and a sense of fun.

In 1902, Ruth enrolled for one semester at Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, and then transferred to Buchtel College (later the University of Akron), where she completed only two terms. Instead of finishing her formal education, she spent a year touring the western United States, writing stories and poems as she traveled.

Her journalistic career begin in August 1907, when she accepted a job as cub reporter with the Akron Beacon-Journal. She rose through the ranks as society editor, music critic, and special interviewer, earning her first byline when she secured a rare interview with Mrs. Henry Ford. By the time she left the newspaper in 1910, she had become the editor of its women’s page.

She then moved to Cleveland for a job as feature writer for the Cleveland Press. In 1910, her career began to blossom when she assumed the pen name of “Ann Addams” and went undercover to report on the harsh working conditions of women in factories and households. During this time, she also wrote poems, fiction serials, and short stories for the paper. She met her future husband, Emmet Finley, also a reporter, while she was doing her investigative writing. The were married August 24, 1910.

Ruth grew up with a knowledge of quilts through her family connections. During her years as a newspaper writer and editor, she began to collect antique quilts. From 1910 to 1919, during the first years of her marriage in Cleveland, and after the couple moved to New York in 1920, she would take little motor vacations along the country roads of Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and New England. When certain quilts hanging on a clothesline caught her attention, she stopped at the farmhouse and asked for a drink of water. With that simple entrée, she elicited from the owners the pattern names and stories of the quilts. Ruth sometimes purchased these quilts to add to her growing collections.

Ruth also collected patchwork patterns, making diagrams and identifying each by name. If more than one name was given to the same pattern, she recorded all variants and eventually included in the her book the one she thought most appropriate. Her meticulous research continued for several years, culminating in the book that was to bring her lasting fame.

The writing of Old Patchwork Quilts and the Women Who Made Them began in 1915 and ended in 1929, a fourteen-year effort. The first quilt book published since Marie Webster’s Quilts: Their Story and How to make Them appeared in 1915, it included information on more than three hundred quilt patterns. Her empathy for the women of the nineteenth century is evident throughout the book.

There is no doubt that this book had a profound influence on quilters and designers of the day, as well as on many who came later. For example, Rose Kretsinger wrote to her asking for a pattern of The Garden quilt. When Ruth replied that she had no pattern, Rose designed her own, using only the black-and-white picture in Old Patchwork Quilts. Several other excellent quilt makers also made versions of The Garden, and three were selected as among America’s 100 Best Quilts of the 20th Century.

Although not a quilter herself, Ruth did design one particular quilt: the Roosevelt Rose, named in honor of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In a 1934 article in Good Housekeeping, she claimed she was reviving “a peculiar and paramount tradition- the creation and naming of new designs in honor of events political, economic, and social.” Photographs and descriptions of the quilt portray it as “a rectangular wreath of fantasy flowers appliquéd in gorgeous bas-relief. A great variety of brilliant calicoes were used for the flowers of the wreath against a background of black sateen. The quilt was lined and corded with lipstick red.

Ruth’s husband shared her interest in collecting antiques, but in 1916, the two discovered a heretofore unexplored common bond- a keen interest in the occult. While waiting for a snowstorm to subside, the two began playing with a Ouija board. To their great shock and surprise, the board spelled out messages from a young American soldier who had been killed while fighting with the French Army in Alsace. Although they first reacted with disbelief, they continued the activity through much of 1917, with Emmet hastily jotting down the messages as Ruth received them.

While their public careers flourished, Ruth and Emmet wrote a book, Our Unseen Guest, published in 1920 under the pen names “Darby and Joan.” They kept this facet of their lives a deep secret in order not to jeopardize their careers or offend their families. Until the cover-up was discovered by Lovina May Knight in 1990, only their publisher and their little group of psychic friends shared the knowledge of their true identities.

Ruth also received messages from “the other side” from her friend Betty, wife of Steward Edward White. Stewart wrote a book called The Unobstructed Universe in 1940, based on these communications. Following Stewart’s death, the Finleys started writing Content of Consciousness, based on messages from Stewart. Emmet became ill and died in 1950, leaving this book unfinished.

Ruth Finley’s last known writing was the start of her autobiography. Fourteen typewritten pages, with penciled margin notes, are all that remain of this attempt. After a lingering illness, Ruth died in Glen Cove, Long Island, New york, on September 24, 1955, the day before her seventy-first birthday. In 1979, Ruth Finley was among the first group to be inducted into The Quilters Hall of Fame.

An early feminist, Ruth Finley promoted quilting as women’s folk art. Through her personal contacts with the quilters and their stories, she recognized the importance of the art of quilting in the lives of American women. In honoring quilters past, Ruth created a work of lasting value. The patchwork quilts that she thoroughly researched and meticulously described have provided valuable historical information for generations of quiltmakers and researchers. The frequency with which she is cited in recent publications reveals the depth of respect still felt for her in the quilt world.

By Virginia Amling

“Yet there is a living reason for all that human fingers create…

Quilt names tell the story of both the inner and outer life of many generations of American womanhood.”

Ruth Finley

Old Patchwork Quilts and the Women Who Made Them (1929) pp. 7-8

Old Patchwork Quilts and the Women Who Made Them by Ruth Finley was one of a few books on quilts written during the first half of the twentieth century in the United States.

Ruth Ebright Finley. Courtesy of William and Margaret Dague.

Selected Reading

Brackman, Barbara. “Old Patchwork Quilts and the Woman Who Wrote it: Ruth E. Finley.” Quilter’s Newsletter Magazine, no. 207 (November/December 1988): 36-38.

Clark, Ricky. “Ruth Finley and the Colonial Revival Era.” Uncoverings 1995. Edited by Virginia Gunn. San Francisco: The American Quilt Study Group, 1995, 33-66.

Finley, Ruth E. The Lady of Godey’s: Sarah Josepha Hale. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1931.

—–. Old Patchwork Quilts and the Women Who Made Them. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1929. Reprint, with introduction by Barbara Brackman, McLean, VA: EPM Publications, 1992.

—–. “Patchwork Quilts.” House and Garden, February 1943, 61-63.

—–. “The Roosevelt Rose- A New Historical Quilt Pattern.” Good Housekeeping, January 1934, 54-56, 100.

For a more information see: The Quilters Hall of Fame: 42 Masters Who Have Shaped Our Art Click here