Ruby Short McKim: Doodler to Quilter

This past Saturday was National Quilting Day, and marked one year since I started writing this blog. My original intention had been to introduce you to the Quilters Hall of Fame Collection because I had been working on the committee that is in charge of that. But the pandemic shelter-in-place policy put a quick end to that and so I shifted to writing about the Honorees. Now, with vaccinations, we should be able to get back to Collections work soon, and I’m looking forward to telling you about our “finds”. In the meantime, this week I’ll write about Honoree Ruby Short McKim.

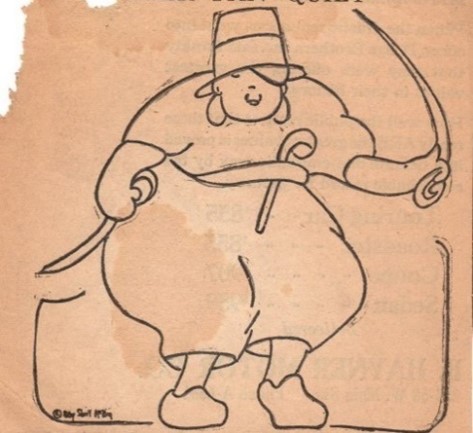

I’ll be the first to tell you that I don’t have the discipline to be a true researcher. Generally, I poke around and find things, but often, I go about it the hard way. This is a case in point. I started out to see what McKim objects, if any, the Hall of Fame has; it turns out that we have quite a few quilts, and you can see them all at the link below. We also have some photos, including one with a block that caught my eye: “Smee the Irish Pirate”. Not knowing who Smee is, I went searching and learned that he is a character in J.M. Barrie’s play “Peter Pan, or the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up”. He’s Captain Hook’s bo’s’un, “stabs without offense” and darns socks for the boys. I suppose if I had kids or grandkids, I might have seen the Disney version and recognized the name. But the McKim version is on her Peter Pan quilt. Now, if I had started with the Peter Pan quilt instead of just that one block, I might have missed Smee, thinking I knew all about the main characters. Here’s McKim’s Smee, Smee played by Edward Kipling in 1924, and a Disney version.

-

Photo: TQHF -

Photo: Wikipedia -

Photo: Mr. Smee gallery Wiki at Fandom, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License

Well, that was a roundabout way to get to the fact that Ruby McKim was known for her patterns, including the Peter Pan quilt. You can take a more direct route by reading the bio information at the link below. And there’s also a link to a great article about McKim’s early years.

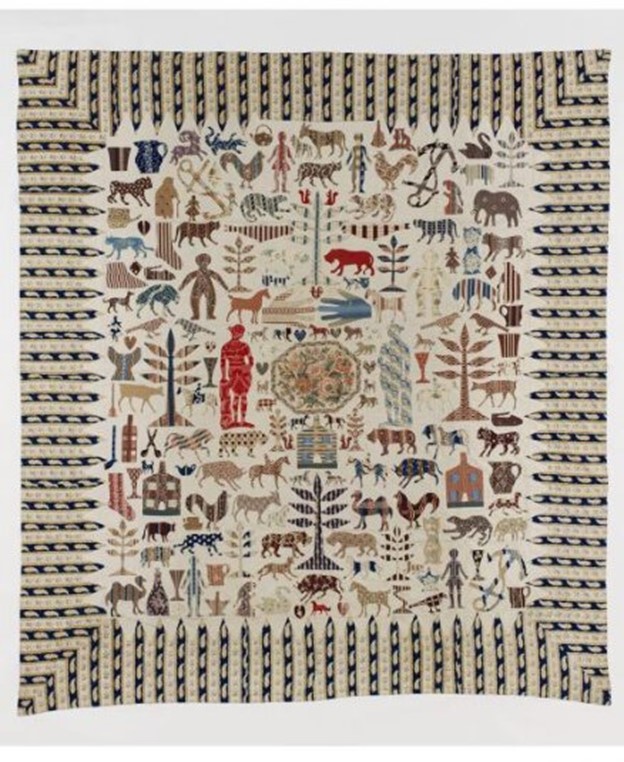

A doodler from an early age, McKim illustrated her high school yearbook and often included little sketches in her letters to family and friends. She did a number of watercolor paintings, including one of Russell Stover’s garden—I didn’t know he was a real person, I just know the candy name. After formal training in New York City (a big move for a Midwest farm girl whose parents were Latter-Day Saints, but-never fear-she stayed with her older sister who was married to a missionary) McKim began her career as an art teacher, but soon seguéd to syndicating quilt patterns. Her first, “Bedtime Stories”, was based on the animal characters of Thornton Burgess, and she called them “Quaddy Quilties”—maybe because the characters were four-footed or was it because they had squared-off shapes? As an aside, Burgess, who was McKim’s fellow columnist at the Kansas City Star, wrote over 15,000 bedtime stories and 170 books, and collaborated with illustrator Harrison Cady. Here are some of McKim’s animals next to Cady’s frontispiece for one of the “Old Mother West Wind” books.

-

Photo: Spoonflower -

Photo: Wikipedia

The McKim Quaddies are available as Spoonflower yardage (maybe because outline embroidery isn’t as popular now as it was when McKim was publishing in the 1920-30s, but we all love panels and color). There’s a link below, and you can also get another design, “Toy Shop Windows”, at the same site.

The original patterns appeared as weekly newspaper installments, generally coming out over a twenty- week period to provide a 4 x 5 straight setting of the blocks (although some, such as “Bird Life” had twenty- four), usually sashed. The Kansas City Star, the Omaha World-Herald, the Nebraska Farmer, Woman’s World, Successful Farming, Indianapolis Star and the Ft. Wayne News-Sentinel were among the papers which carried her patterns. Each design for the Peter Pan quilt was accompanied by McKim’s fanciful telling of the story. For example, Smee was said to be fat and jolly because he enjoyed pirating so much; the Father slept in Nana’s doghouse because, even though he was usually stern and dignified, he had remorse for leaving the children without their protector; Tinkerbell appeared as “a tiny darting light like a fire-fly or a wee tinkly noise so faint that you’d just imagine it wasn’t a sound at all.” The placement of the blocks in the “Peter Pan Quilt” was also specified: corner blocks were identified because their curved outlines were a design element. This is a listing of the series quilts, several of which can be found on the Quilt Index:

Quaddy Quiltie, Mother Goose Quiltie, Nursery Rhyme, Rhymeland Quilt, Roly-Poly Circus, Fruit Basket, Flower Basket, A Jolly Circus, Child Life Quilt, Alice in Wonderland Quiltie, Flower Garden, Bird Life or Audubon Quilt, Three Little Pigs, Colonial History, Bible History, Farm Life, Peter Pan, State Flowers, Wildwood Flowers, Toy Shop Window, Patchwork Sampler, Parade of States, and American Ships. (Let me know if I missed any.)

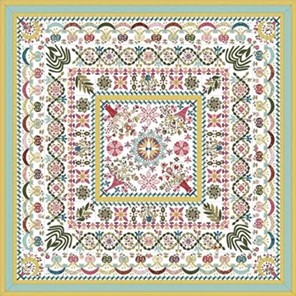

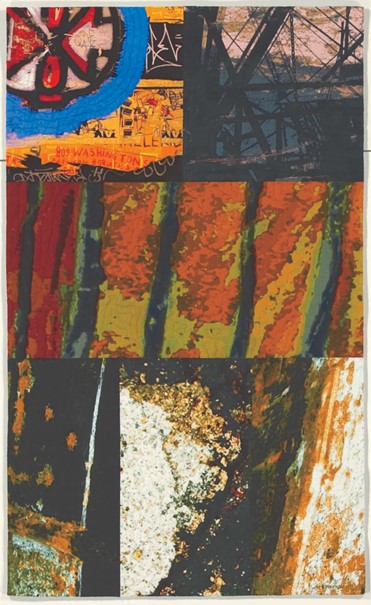

Here’s a quilt from the “Flower Garden” series with an alternate plain block setting and a special border.

And here’s “Roly Poly Circus” with a traditional setting.

In addition to the newspaper outlets, McKim’s designs appeared for several years in Child Life magazine. One of the features, appearing in 1923, was “Fables in Fabric” in which a fable was printed in one column and an illustration of the fable (suitable for embroidery) was next to it. Included in this series was “The Fox and the Grapes”, “Tortoise and Hare” (intended to be a counterpane), “Goose That Laid the Golden Egg”, “Wise Owl and Foolish Grasshopper”, and (designed for a laundry bag, although I don’t see any connection between image and use) “Frog Who Looked Before He Leaped”. McKim illustrated the first fable, but other illustrators interpreted her sketches for the final fables.

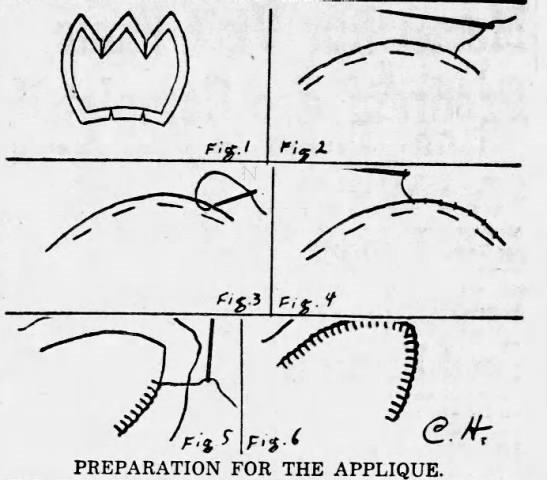

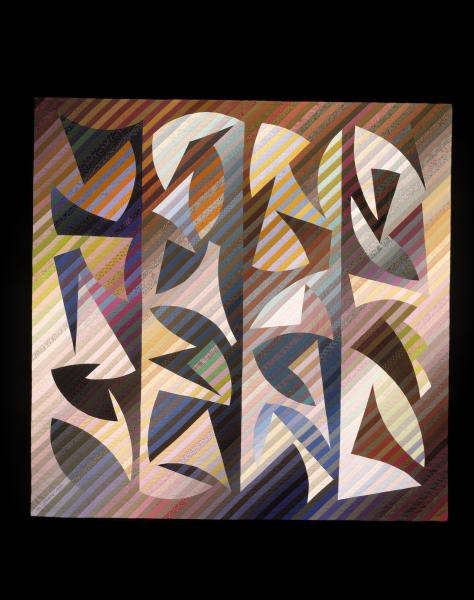

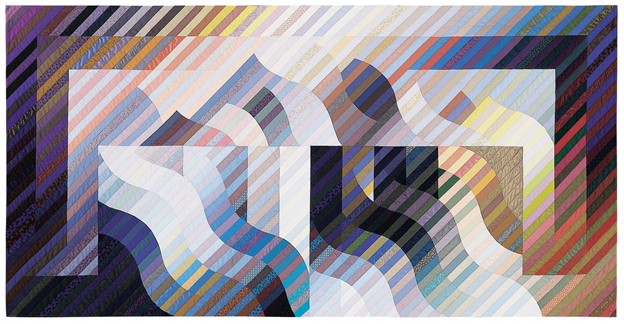

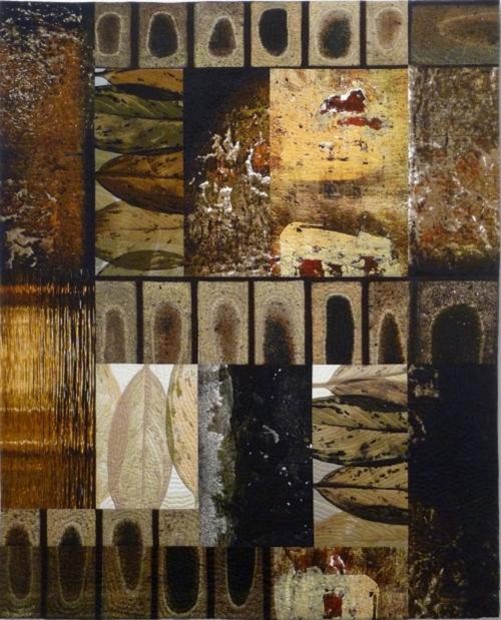

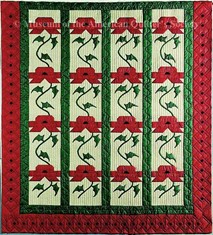

By the late 1920s, the Colonial Revival caught up with McKim, and her work expanded into appliqué and piecing. McKim published two catalogs, Designs Worth Doing, and Adventures in Needlecraft. Individual patterns from the Designs series are available on Etsy, and you may find some from Adventures as well. Here’s a quilt from those catalogs, made by Rosie Marie Werner, an expert on kit quilts:

I can’t tell whether to call this style Art Deco or to just say it’s reminiscent of McKim’s other quad/square designs. Either way I like it, so here are two more stylized floral McKim quilts.

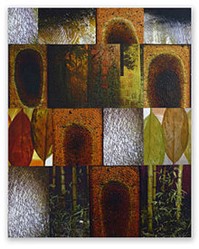

-

Thieme, Leureta Bea. Oriental Poppy. 1987. From National Quilt Museum Collection. Published in The Quilt Index, https://quiltindex.org/view/?type=fullrec&kid=10-7-323. Accessed: 03/21/21 -

Hunsicker, Barbara. Patchwork Pansy. 1950-1975. From Arizona Quilt Documentation Project. Published in The Quilt Index, https://quiltindex.org/view/?type=fullrec&kid=38-36-4108. Accessed: 03/21/21

If you want a break from quilt-making, but still want to be quilt-connected, Designs Worth Doing is being re-imagined by McKim’s granddaughters as Designs Worth Coloring. This series combines Ruby’s floral designs with zentangle backgrounds; books are available at the McKim Studios site below. (This is probably a good point at which to say that you can find all things Ruby Short McKim, including a notecard of that Russell Stover Garden watercolor, at this site. Happy shopping!)

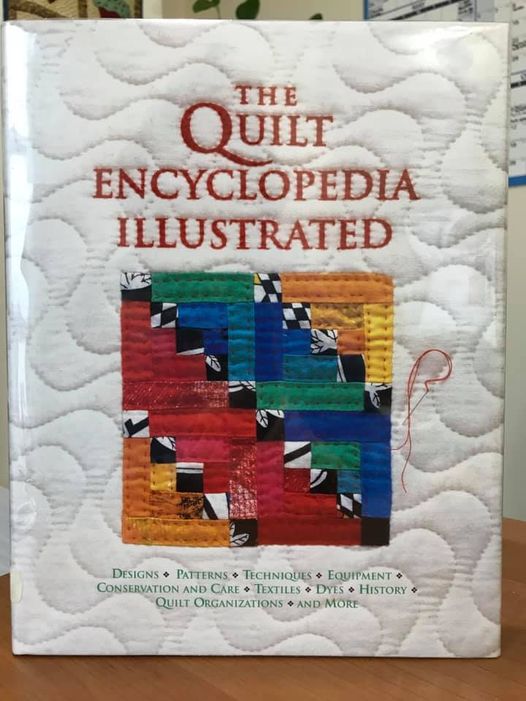

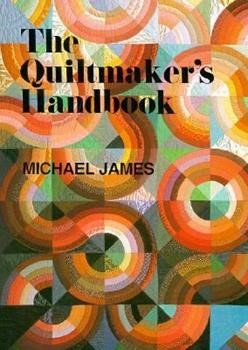

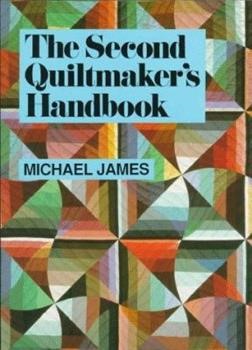

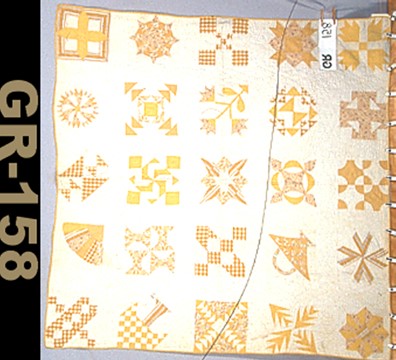

Ruby Short McKim may be best-known to day as the author of 101 Patchwork Designs, published in 1931 and re-issued by Dover in 1962. It originally had a lavender cloth cover, but now looks like this, or this, or this:

Don’t be fooled like I was; they’re all the same inside—only the cover is different. I own all three.

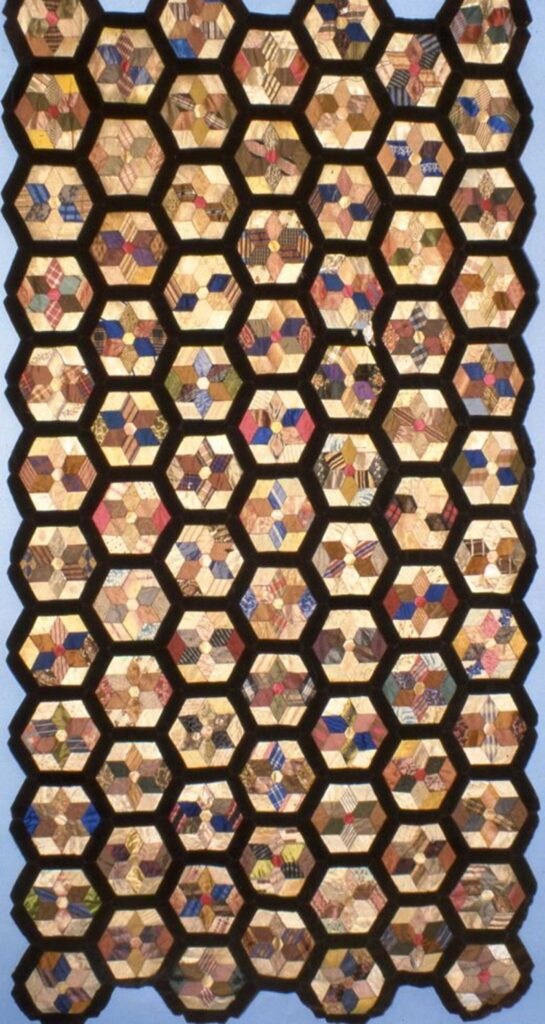

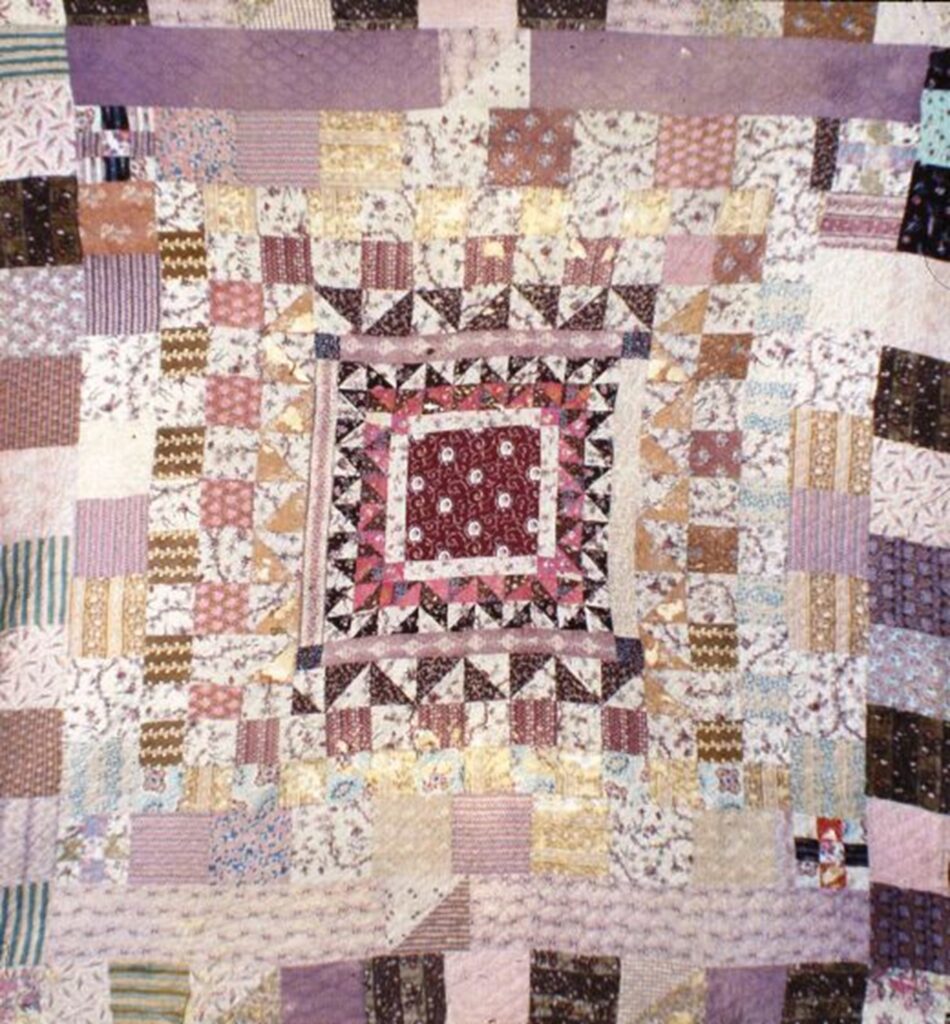

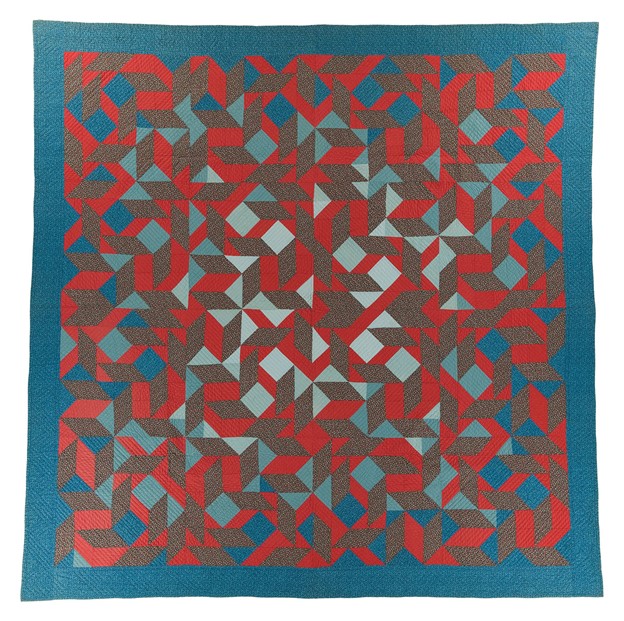

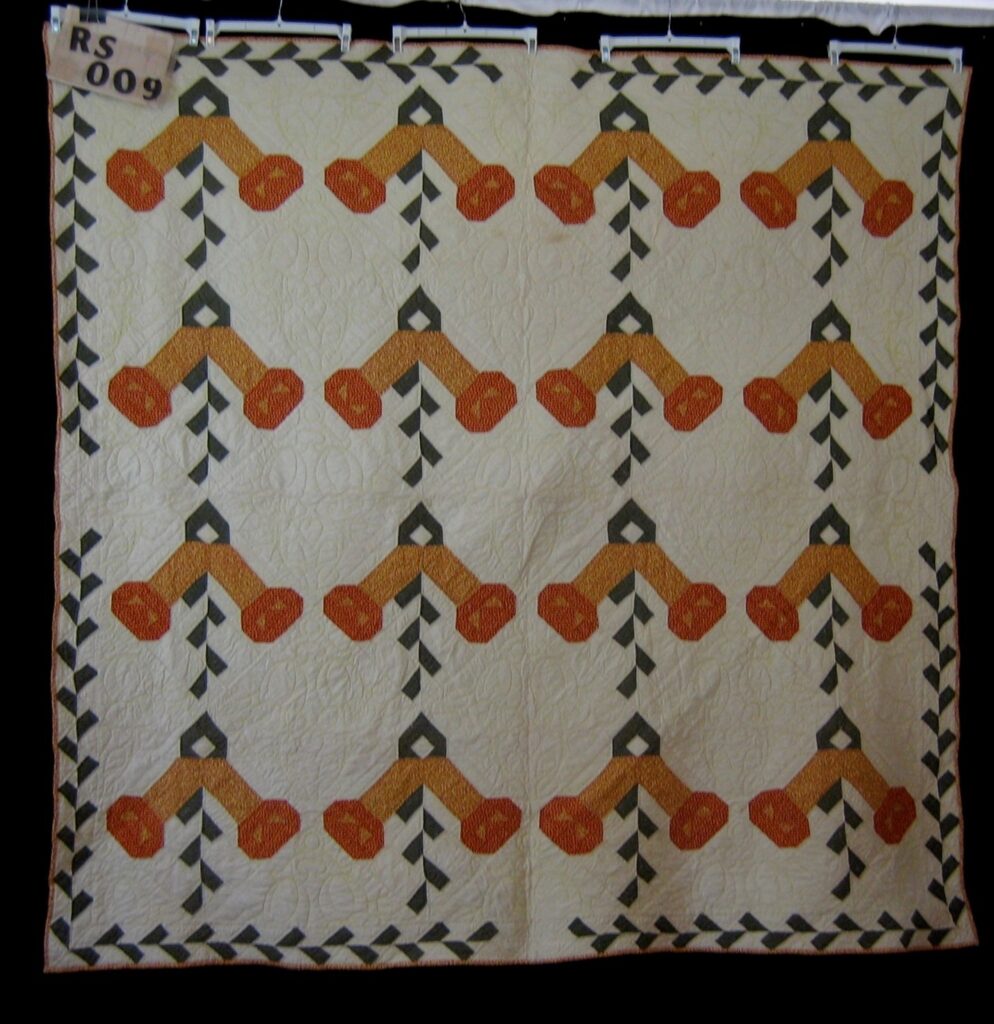

Some of the block designs were also patterns for a sampler published in the Kansas City Star. Here’s a quilt made from that series; You can find lots of samples in mixed colors, but this limited palette is unusual.

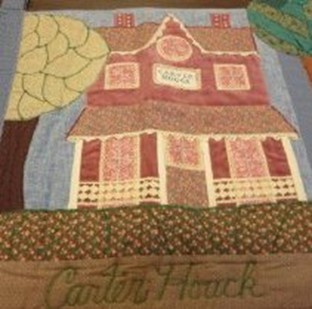

Now I’m going to close with one final McKim picture, a “House on the Hill” block from the Kansas City Star.

I have four of these blocks, and wonder what to do with them. The Quilters Hall of Fame already has one donated by Honoree Cuesta Benberry, so they don’t need more. I could set them into a small quilt, but they really aren’t my style. “Why did you buy them?” you ask. I’m at a loss to explain; I knew they were something historical, but that doesn’t help. Please send suggestions.

Your quilting friend,

Anna

TQHF McKim objects. https://quiltershalloffame.pastperfectonline.com/webobject?utf8=%E2%9C%93&search_criteria=McKim&searchButton=Search

Bio info. https://quiltershalloffame.net/ruby-short-mckim/

Early years. https://quiltindex.org/view/?type=page&kid=35-90-203

Quaddy fabric. https://www.spoonflower.com/en/fabric/5803123-quaddy-quiltie-by-ruby-short-mckim-by-mckim_studios

McKim Studios. http://www.mckimstudios.com/index.shtml