Marguerite “The Cat” Ickis

How did you learn to quilt? In my case, no one in my family was a quilter, so I was introduced by a friend. I purchased four block of the month kits from JoAnns and gave it a try. Then I started reading. I got Harriet Hargrave’s Quilter’s Academy books (freshman and sophomore years only—I was an academy drop out), Ruby Short McKim’s One Hundred and One Patchwork Patterns, a number of how-to books and a few coffee table books for inspiration. If I had been born 50 years later, I’d probably have just looked on the internet and found Alex Anderson and Jenny Doan.

But what would I have done if I had been born 50 years earlier? I would have read Marie Webster (Quilts: Their Story and How to Make Them), Ruth Finley (Old Patchwork Quilts and the Women Who Made Them), and Marguerite Ickis (The Standard Book of Quilt Making and Collecting. These classics are part of the quilt historian’s essential library, and are still available on eBay and the open market. Today I want to tell you about one of these authors.

If you read the bio on the Hall of Fame website (link below), you’ll see that Marguerite Ickis re-invented herself many times over. Her way of putting it was that she had nine lives–hence “The Cat”. We know her from her quilting books, but she’s known for much more. But before I get to that, here are the quilting books.

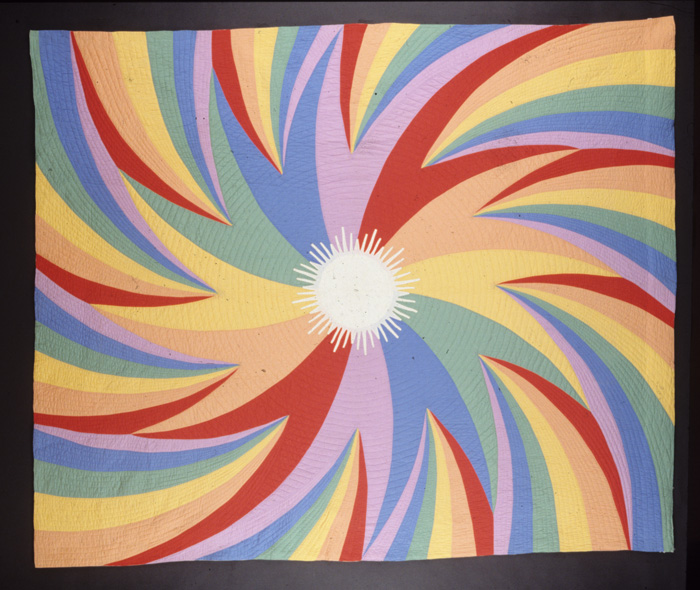

-

-

-

5 -

-

The “Standard” book is just that, an all-inclusive handbook. To give you an idea of its scope, here’s what the publishers say about it:

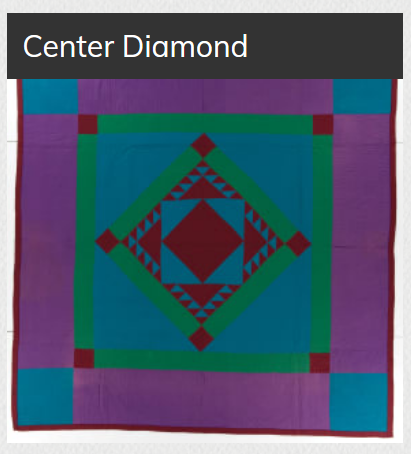

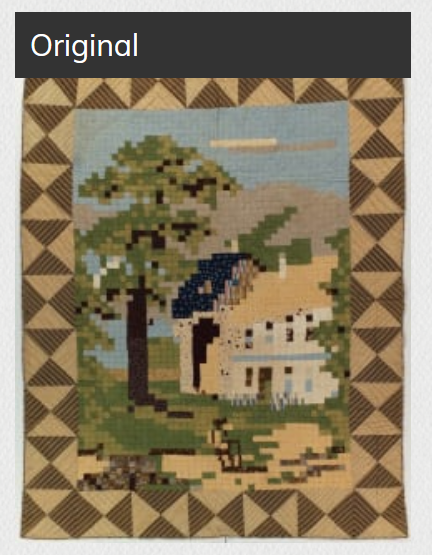

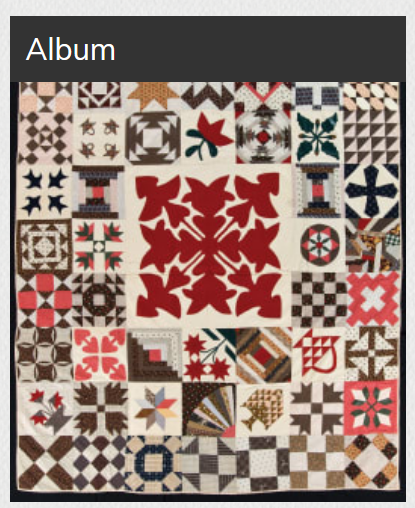

| You’ll learn how to plan the quilt, the number of blocks to fit a bed, how to select the pattern to harmonize with the design and color of the room, and how to choose materials. Clear directions explain how to cut, sew, and make applique patterns, patchwork, and strips. An entire chapter on design discusses basic elements, sources, making your own designs, avoiding sewing problems, how to use the rag bag, and much more. The section on patterns gives directions on tracing, seam allowance, and estimating quantity. There is full information on borders, quilting, and tufting, and just about every other aspect of quilt making. Mrs. Ickis shows you over 100 traditional and unusual quilts, including Basket, Tree of Life, Flowers in a Pot, Traditional Geometric, Friendship, Square and Cross, Saw Tooth, Drunkard’s Path, Flying Geese, Mexican Cross, Pennsylvania Dutch, Crazy Quilts, Yo-yo Quilts, Album Quilts, and dozens of others, including over 40 full-size patterns. You are given other uses for quilting, such as drapes, curtains, upholstery, lunch cloths, purses, cushions, and Italian quilting. Completing the coverage are fascinating chapters on collecting quilts as a hobby; how to make full-size patterns of famous American quilts from pictures, small designs, and museum or collector’s quilts; and a history of quilt making with personal memories. |

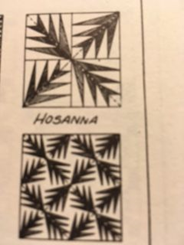

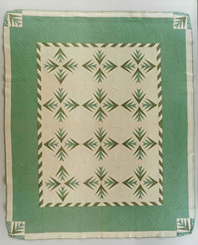

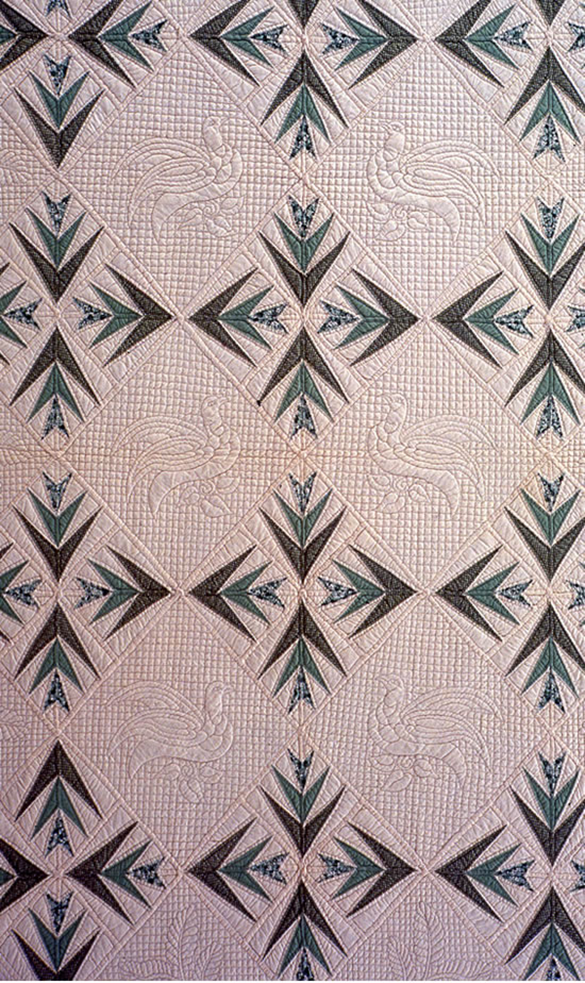

All this for under $5.00 at today’s prices! But a word of caution: the directions may not be so simple. Here’s how to make a Caesar’s Crown block: “Fold block diagonally each way across center and then across to get center creases. Draw in 2 circles. Use compass to draw center block. The tops of the diamonds will come along the fold in the block. Piece design and appliqué to block.” Here’s the block, in case you can’t visualize it from the directions:

Even so, the book is more than worth the cost for this famous quote from an unknown Ohio great-grandmother:

It took me more than 20 years, nearly 25, I reckon, in the evenings after supper when the children were all put to bed. It scares me sometimes when I look at it. All my joys and all my sorrows are stitched into those little pieces. When I was proud of the boys….When the girls annoyed me….And John too….Sometimes I loved him and sometimes I sat there hating him as I pieced the patches together. So they are all in that quilt, my hopes and fears, my joys and sorrows, my loves and hates. I tremble sometimes when I remember what that quilt knows about me.

Wow! If that doesn’t make quilting into something magical and mystical, I don’t know what would.

With an undergraduate degree in education from Ohio University and a master’s in botany from Columbia, Ickis’ first career/”life” was as a teacher. Before going to Columbia, she was an instructor in recreation at New York University and Dean of the New York Recreation Training School. She then went East to work as the curator of the Botany Department at the Massachusetts Agricultural Experiment Station (Mass. Agricultural College) in Amherst.

Following that “life,” but related to it, was a career with the Girl Scouts. Beginning with the Paterson (New Jersey) Council in 1923 as a “first class nature specialist”, she went on to direct the acclaimed nature museum at the Council’s summer camp. She spent almost a decade working with the Girl Scouts as a trainer at the national level, and was affiliated with the National Recreation Association as a member and as Assistant Editor of “Recreation” magazine. She was also Dean of the Recreation Training School for the Works Projects Administration (WPA). This was a time when the “Playground Movement” was coming into its own, and Ickis would be glad to know that there is a playground named after her in Massachusetts.

Playground on Cape Cod named after Marguerite Ickis. See more at link below.

A few of Marguerite Ickis’ “lives” came from difficult circumstances. When she was around 60, she began losing her sight to cataracts. Rather than retire, she did two things: she started painting and she opened a restaurant.

The restaurant was located in the town of Dennis on Cape Cod. She poked fun at herself in this “life” saying that even though she had no restaurant experience, she could see enough to measure three cups of flour and one cup of lard for a pie crust. She ran the restaurant for fourteen years, and “The Pheasant” is still at the original location, serving freshly-caught seafood and other food cooked on an open wood fire. This new popular restaurant is a far cry from where Ickis started her foodie career. As she explained, “My building had been a storehouse for clipper ships on the Dennis shore and had been moved to Main Street. There was a stall in it which housed a horse and it certainly smelled terribly. We used grills. I had no screens. And do you know the Rockfellers, Fleischmans and others of that ilk came often and loved it.” (“Dennis Author-Painter Still Lives Valiantly,” Women’s World, 1978). I’m including photos of the new restaurant—because I miss going out to eat in pandemic times, and this makes my mouth water. See the link below for their Facebook page; if you are in the area, they have take-away these days.

Ickis also took up painting. She said she wanted to stop chain smoking and using a paint brush gave her something to do with her hands. Her paintings have been likened to Grandma Moses, but she thought they were less stick-like. In fact, she tried to make them homey and personal. One painting is a reminder of the shopping trips with her mother and sister at Stone and Thomas in Ohio to buy new hats—one every year for Easter and another for the county fair. Another is based on people from her childhood town: the butcher and his wife, the man with the ear trumpet, the woman who nursed her baby “right in church”.

Marquerite Ickis’ painting of a quilting bee.

You can see more of Ickis’ paintings in “The Ickis Room” of the Dennis Senior Center, Dennis MA—if we ever get to travel again.

Ickis had a well-established “life” as a writer. In addition to her quilting books, she had several titles related to crafts, hobbies and the “Playground Movement”. Among these are Nature in Recreation, Pastimes for the Patient, The Book of Games and Entertainment the World Over,Weaving as a Hobby, The Book of Arts and Crafts, Folk Arts and Crafts, and Handicrafts and Hobbies for Pleasure and Profit. Garnering the most hits on Newspapers.com are articles about Ickis’ holiday books. Between 1965 and 2000, journalists all over the country relied on her for filler in their feature stories whenever a holiday came around. In October, Ickis was cited as attributing Jack-o-lanterns to the Irish; in the Spring she was quoted on the origin of Easter egg hunts. And at Christmas time, the papers trotted out her craft ideas for holiday decorations. Here are the holiday books:

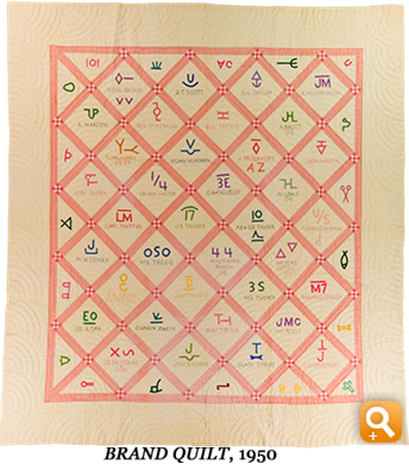

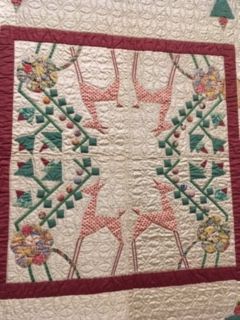

I want to close by coming full circle in Marguerite Ickis’ nine lives, and end with her life as a quilter. This was probably her first “life”; she learned to quilt at a young age in Ohio. She was taught to quilt by her mother and Quaker grandmother and she helped batt quilts with wool produced on the family sheep farm. The Quilters Hall of Fame is very lucky to have an Ickis quilt; this one was made with scraps of costumes from WPA theater productions. (Thanks for the donation, Holice Turnbow!) There’s a link below for more information about the quilt.

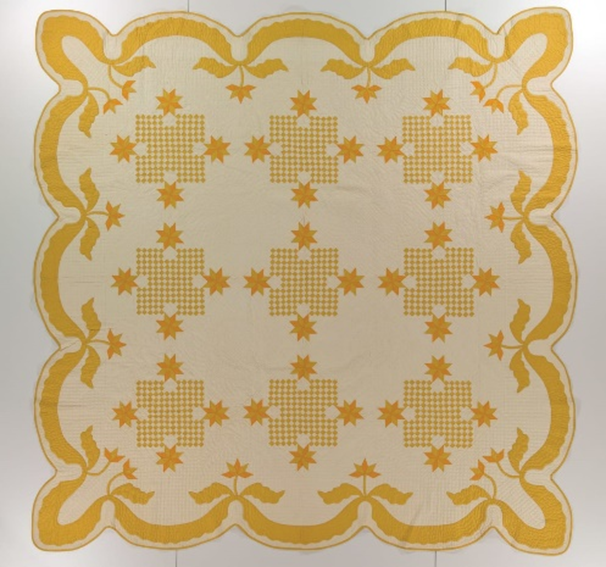

Marguerite Ickis. Fan Medallion c. 1940

Well, that’s the many “lives” of Honoree Marguerite Ickis. I think I would have enjoyed knowing her; she had a sense of humor and self-deprecation as well as a determination to make the most of the hand she was dealt. Worthy traits to emulate.

Your quilting friend,

Anna

Hall of Fame bio https://quiltershalloffame.net/marguerite-ickis/

Ickis Playground https://capecodplaygrounds.blogspot.com/2015/05/johnny-kelley-park-dennis.html

Restaurant. https://www.facebook.com/thepheasantcapecod/

Fan Medallion quilt https://quiltershalloffame.pastperfectonline.com/webobject/342CC602-9798-4B42-AA73-866582057530