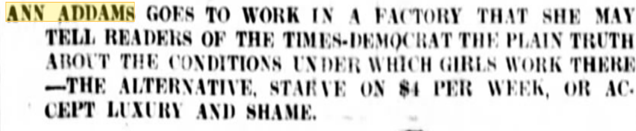

Yvonne Porcella: Color and Inspiration

We could probably all use a little whimsy right now, and there’s no Honoree more whimsical than Yvonne Porcella. You may already know her as the founder of SAQA (Studio Art Quilts Associates) or you may be familiar with some of her colorful work; or she may be totally new to you, and someone you should get to know. I’ll try to give you a good perspective on her and maybe even be able to poke around and find something you didn’t know.

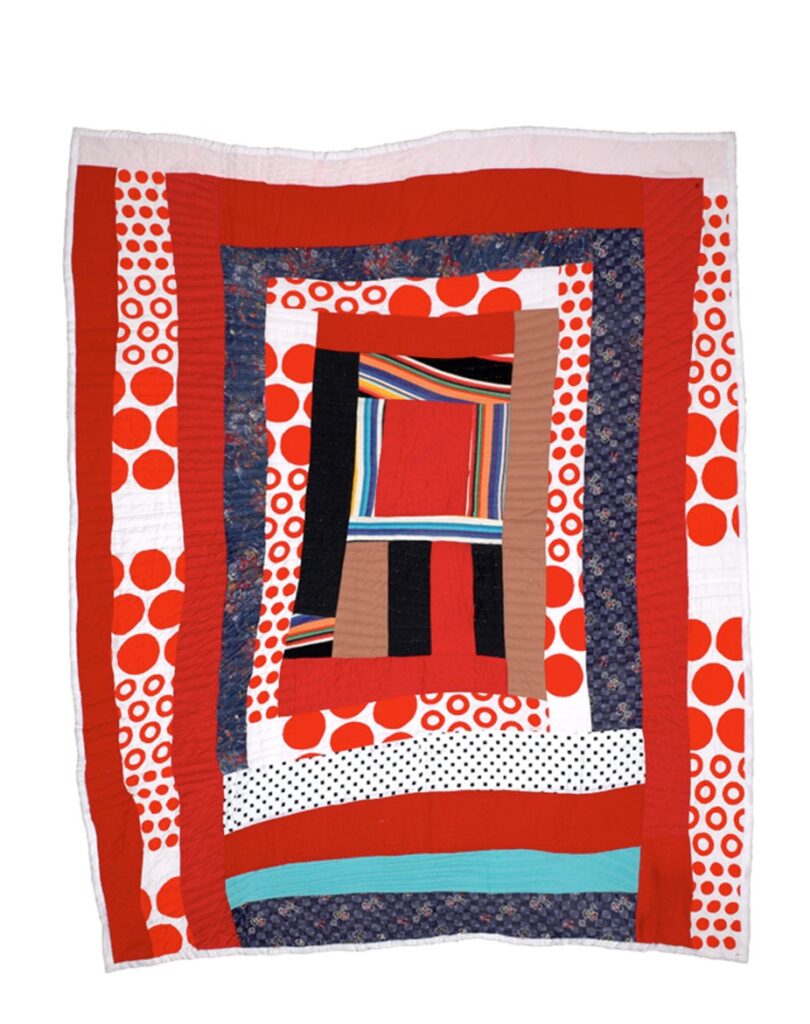

In an interview for SAQA (see link below), Yvonne modestly admits she was honored by the Quilters Hall of Fame because of her pioneering of wearable art. But she shouldn’t have been so self-deprecating because there’s a lot more to her textile career than that. As a self-taught creator she has had at least three distinctive fiber styles, starting with weaving and wearables, moving to bold colors with stripes and checkerboards, and finding calm with silky nature-inspired pieces. You can read her story at the bio link below, and I’ll fill in with some photos and other information.

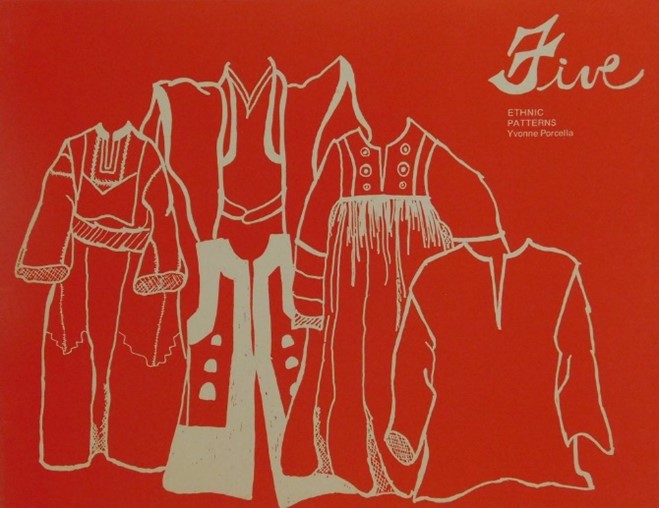

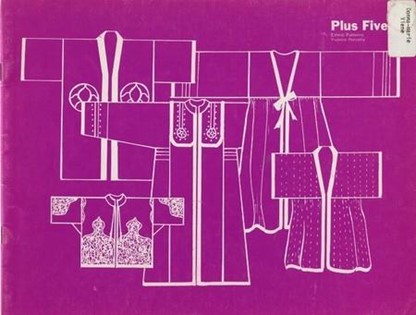

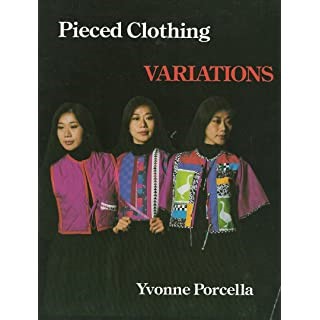

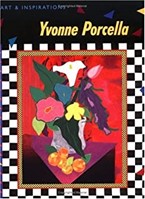

I think Yvonne would have described herself as first and foremost an artist or creator, but she was also an author and teacher. A glance at the book titles that are available on Amazon and elsewhere gives you a good idea of how varied her work was.

Her first two books show the influence of her California hippie connection. That’s my era too, and I remember peasant wear and what would now be called boho style. The kimonos she designed as clothing would evolve into large-scale art for the wall. You can see some nice example of her early clothing at the San Francisco Fine Arts link below.

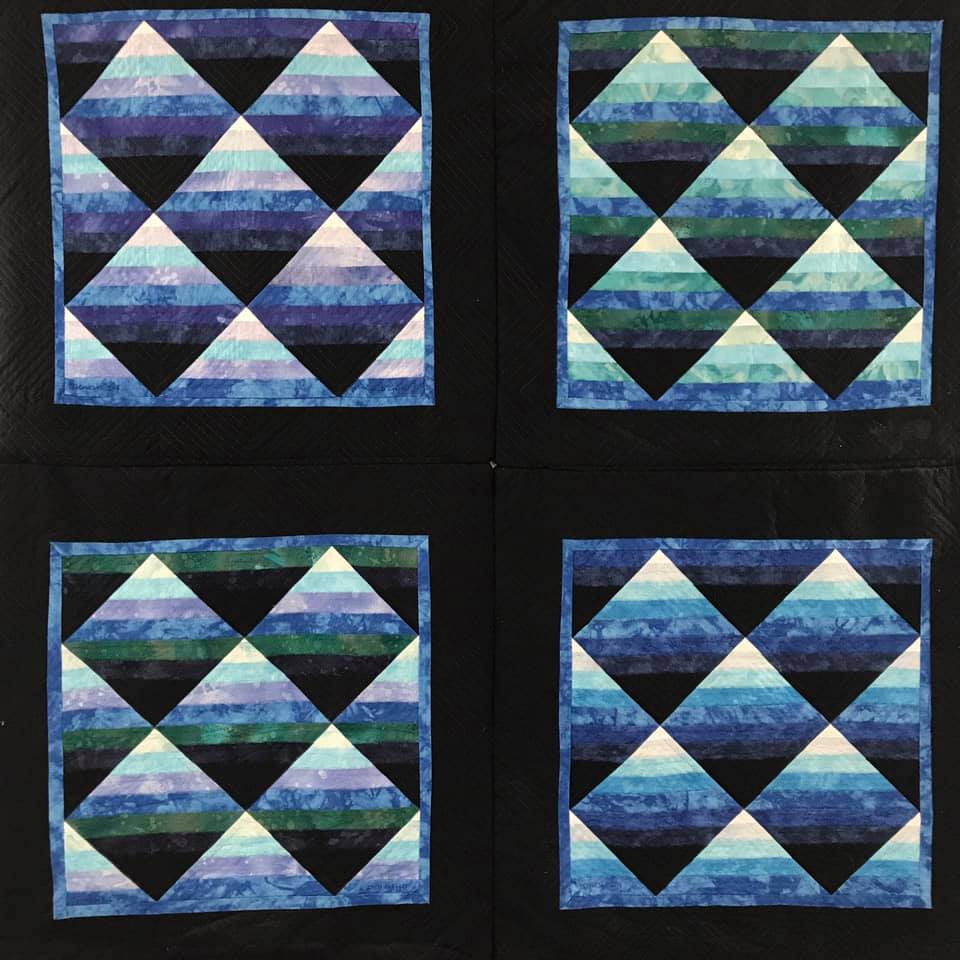

In the next books, you get the flavor of Yvonne’s love of color, and see that she has moved from clothing to quilted expressions. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a picture of Yvonne Porcella where she isn’t wearing something in bold combinations of color, often set off by black and white. Here’s a great photo of her, followed by the “color” books. I can’t say which is brighter.

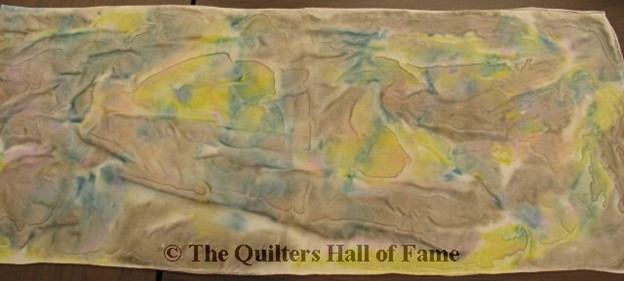

And last comes her beautiful hand dyed and painted fabrics. The Quilters Hall of Fame is fortunate to have one of her silk scarves, and it is so ethereal that the photo can’t capture its beauty. Here’s the book and the scarf.

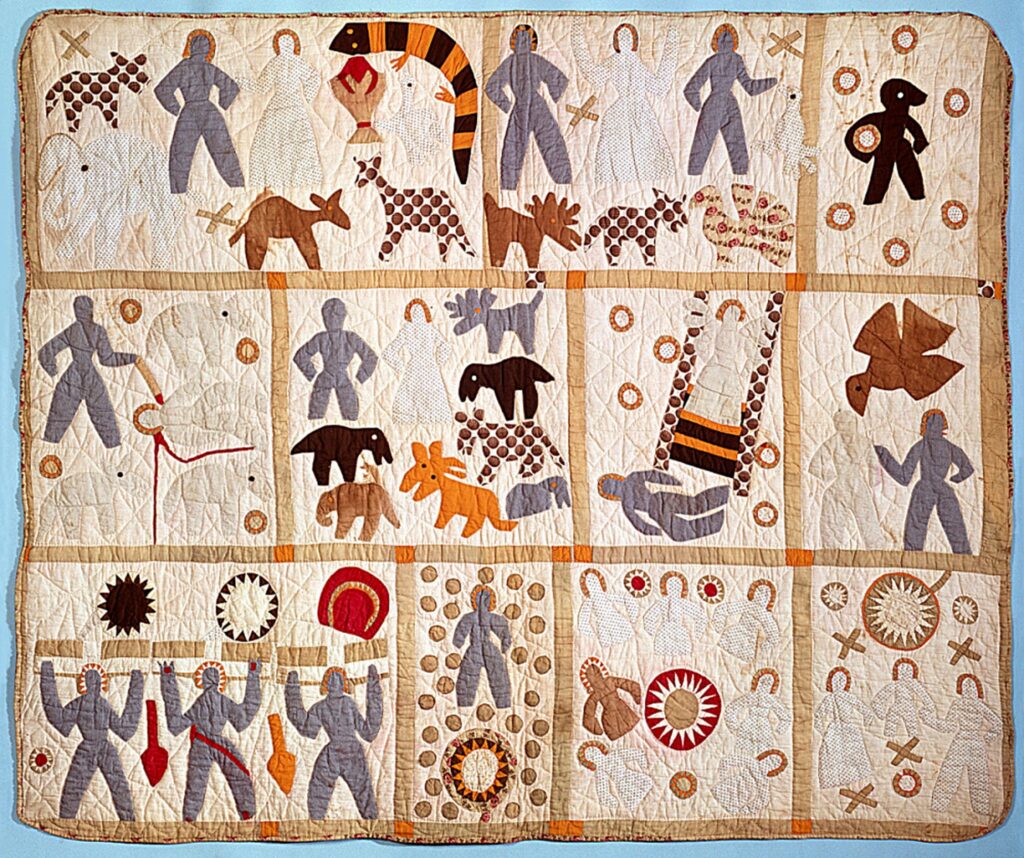

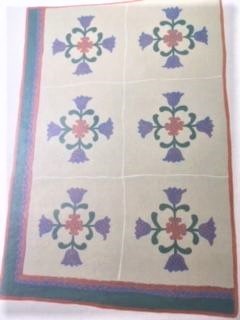

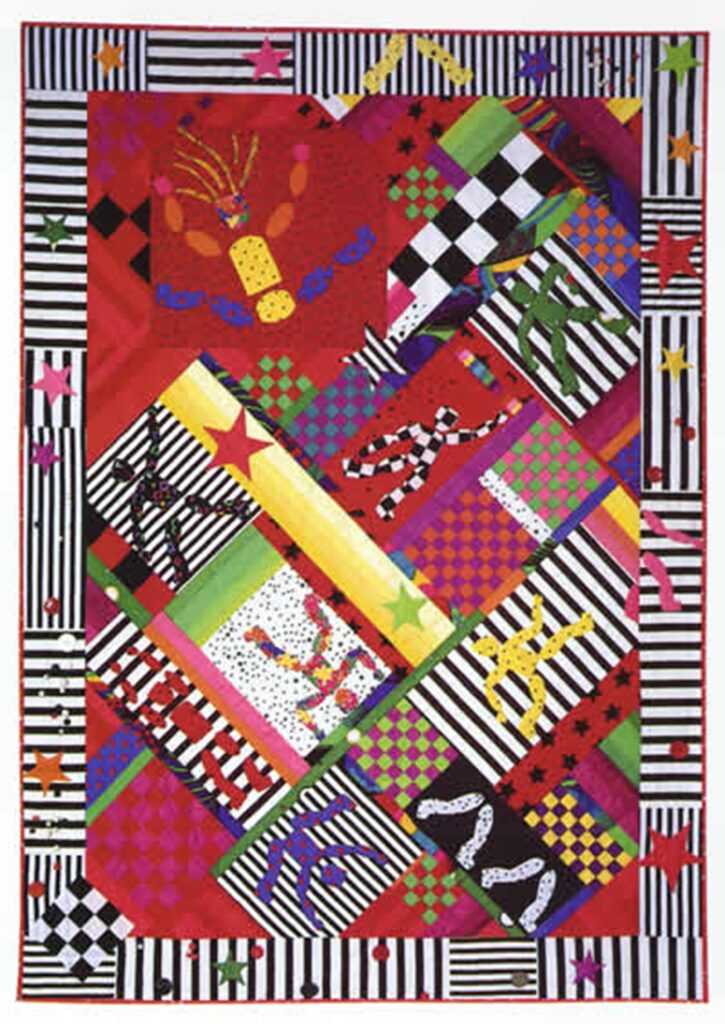

Let me go back a minute to color and show you a quilt that Porcella once owned and is now in the Quilters Hall of Fame collection. This is called “Halloween Quilt”, obviously for the orange and black border and framing squares. But it’s otherwise a riot of color—it’s not necessarily Porcella’s saturated colors, because it’s a 1930s quilt, but nevertheless, it has so many hues thrown together and in that sense it’s very simpatico with Porcella. There’s an interesting story in the link below explaining what this quilt meant to Porcella and how it got to quilt historian and Honoree Merikay Waldvogel who later donated it to TQHF. If you have access to Arts and Inspiration, (the book above with the checkered-bordered quilt) page 127 has a picture of the quilt on the bed in Yvonne’s guest room.

I’ll give you a few examples of how Porcella took inspiration from this quilt and used color in her own works…

Those three photos were taken from Yvonne’s blog, which is still up despite her passing. There’s a link to it below if you want to see more from her. There’s also a link to the Alliance for American Quilts website which has a gallery of Yvonne’s quilts and other information about her. Or you can just look at the Pinterest link and be overwhelmed.

Now let’s look at some of Porcella’s other work. I’ll have some examples, but Yvonne herself will show you one of her last series in the link below; it’s labelled “olive stuffing”, and if you follow the link, you’ll not only see some marvelous pieces, but also learn about the olive connection.

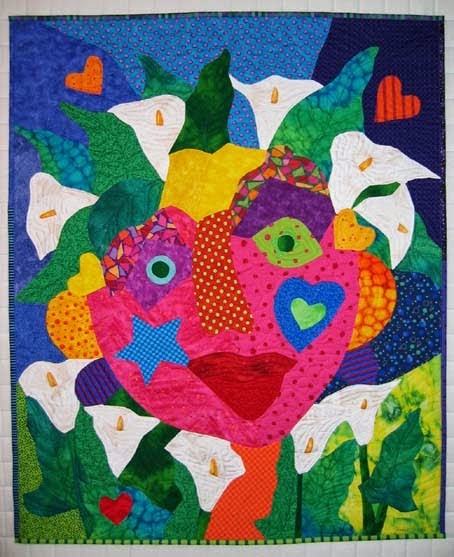

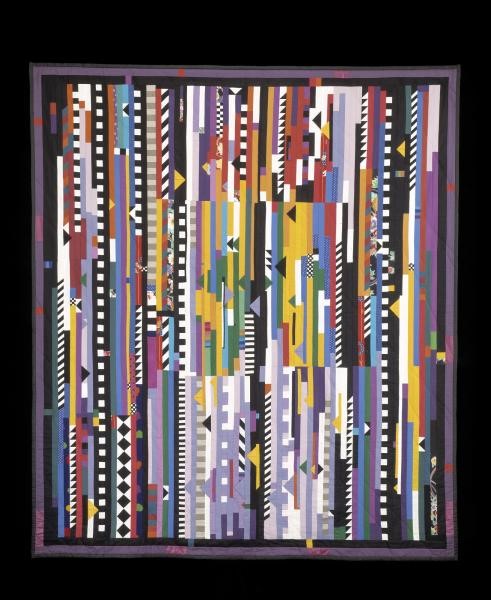

Like several other Quilters Hall of Fame Honorees, Yvonne Porcella has a quilt in America’s 100 Best Quilts of the 20th Century, “Keep Both Feet on the Floor”. This is a quilt about falling and recovering from injuring her knee; I have a friend who is in therapy following knee replacement surgery, and I can guarantee she isn’t experiencing as much fun as this quilt shows—but Yvonne was nothing if not fun. Here’s the quilt:

And here’s Yvonne’s first “art” quilt, made in 1980. It’s called “Takoage.”

Where did her ideas come from? At first, she says that at first it was just color, and you can see that in “Takoage” . She also, like many quilters, was inspired to make quilts for each of her grandchildren, and every one of those quilts is made of bold colors. But one of the things that sets Porcella apart from the many is that for her, inspiration was everywhere: a pet cemetery, an art museum, a personal experience, a visit by the Pope to a nearby town, a road trip, fast food, etc. For me, a goal would be able to say, “The sky’s the limit” in choosing the subject of a quilting project (I’ll never be that spontaneous, but it could be a goal); for Porcella, there was no limit.

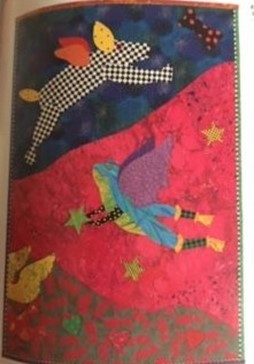

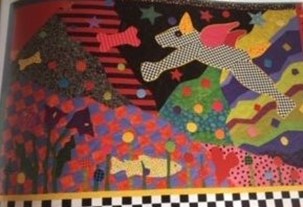

Porcella did a lot of work-in-series, and many of her pieces have images that appear over and over in her work. One of my favorites is a flying dog; sometimes he’s checkered, sometimes he’s purple, once he had green hair, but he’s often chasing a bone and he always looks like he’s having the time of his life.

-

Dog, Frog and Cherub. 1995. Private Collection. Photo from Arts and Inspirations -

Biscuits, Triscuits and Bones. 1997. Private collection. Master Art Quilts, lark Publishing. Photo by Sharon Risedorph.

Another of Porcella’s series was her kimonos, inspired by a display of Asian clothing at an art museum. At first she made wearable works, but she changed her scale and went on to large wall pieces. The first one below is over ten feet long and almost seven feet wide.

This kimono quilt was inspired not by snow, but by another weather-related event. Once, while teaching at the International Quilt Festival in Houston, Porcella was confined to her hotel room for three days due to a hurricane. Festival producer and TQHF Honoree Karey Bresenhan gave her a quilt book as a memory of the experience and it included a circus-themed quilt showing Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee. Those two figures, made with squares and half square triangles, were incorporated into the quilted Haori coat. What a contrast between these two kimonos!

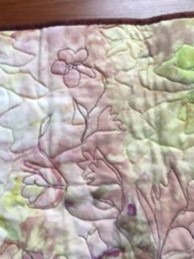

I feel like we need a break from brightness, and fortunately, Porcella can provide that too. She worked extensively with silks which she dyed herself. You saw the scarf example above; now for your moment of Zen, here are two of her nature-inspired works:

Don’t you feel more relaxed now?

If I haven’t yet told you something you didn’t know about Yvonne Porcella, I have two last things. First, she collaborated with Julia Child in the 2000 Oakland Museum exhibit Women of Taste: A Collaboration Celebrating Quilt Artists and Chefs. Their subject was Nicoise salad, and I would love to find out what Porcella came up with for that. If anyone has information, please let me know.

Second, her son, Don is also an artist. He’s best known for pipe cleaner sculptures and installations using popular craft materials. His works often make fun of absurd consumerism and the human condition. And what this says about Yvonne Porcella is that she has encouraged creativity: through display of her own work, through teaching, through SAQA, and even through the way she brought up her children. What an inspiration!

Your quilting friend,

Anna

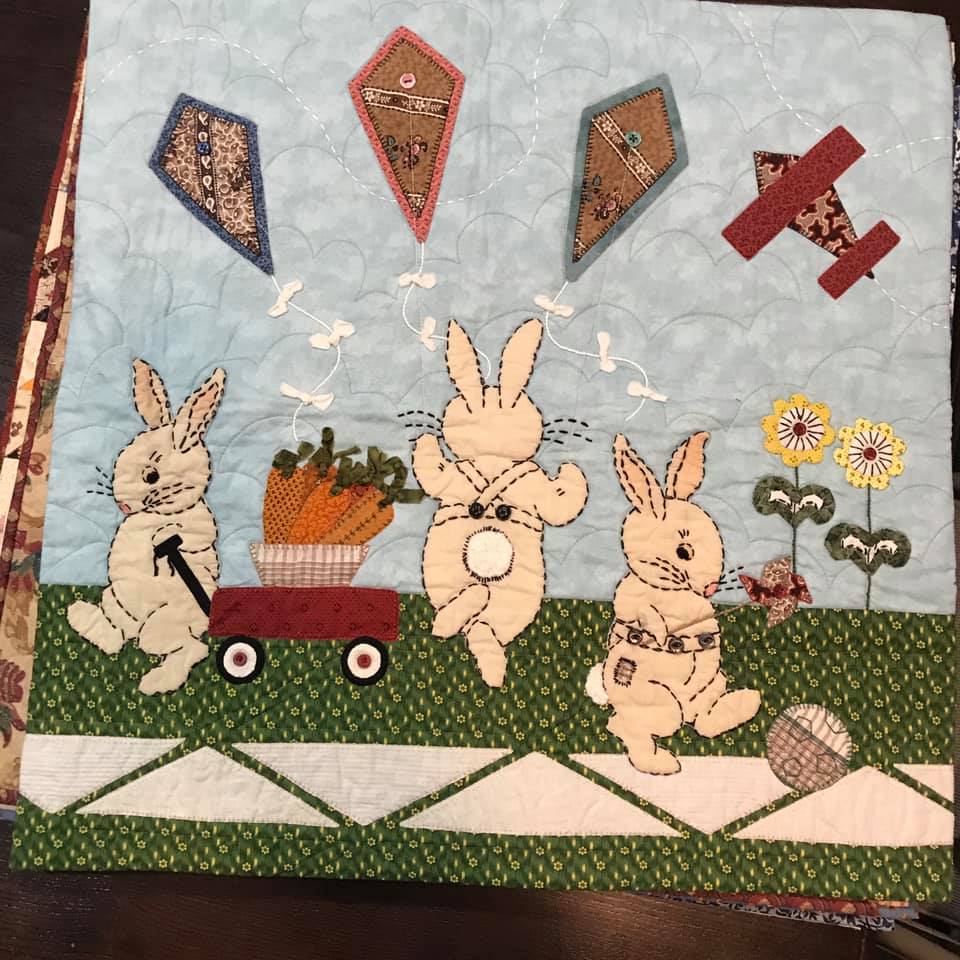

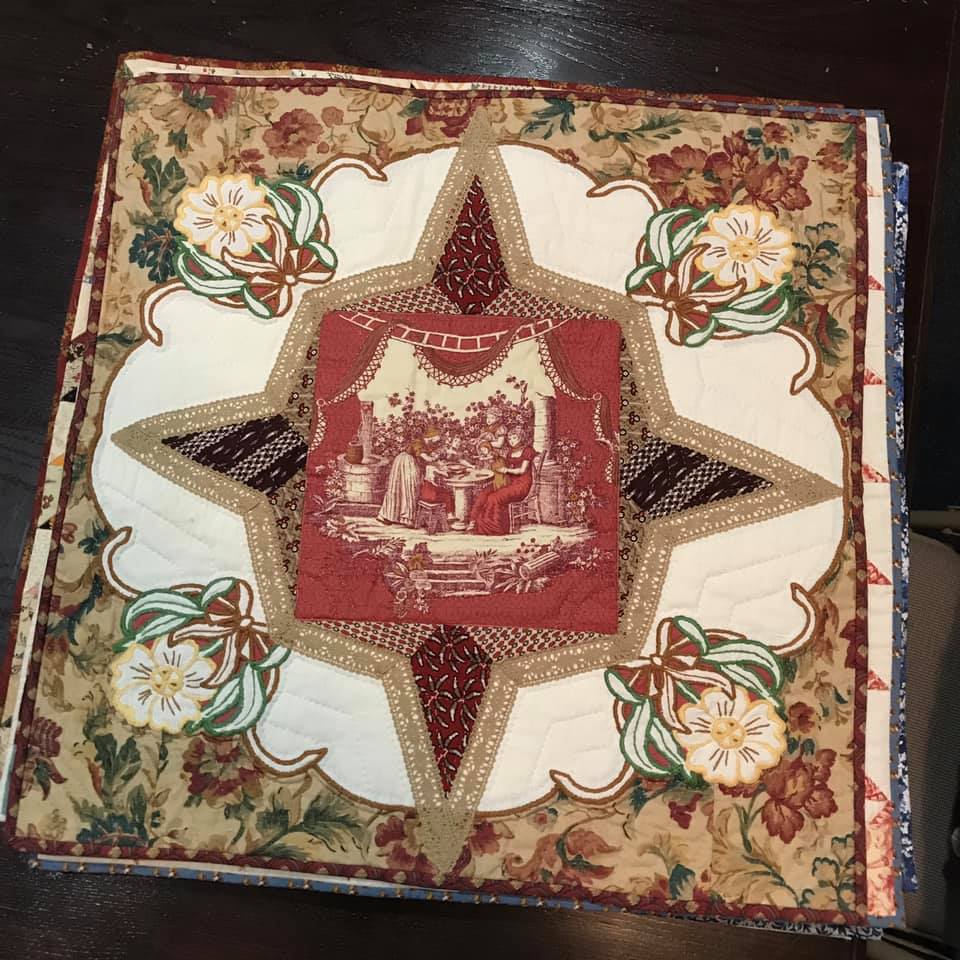

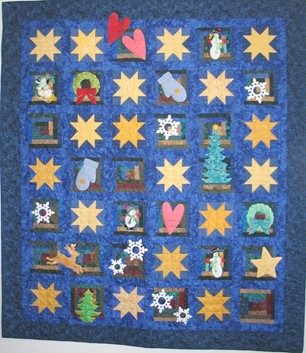

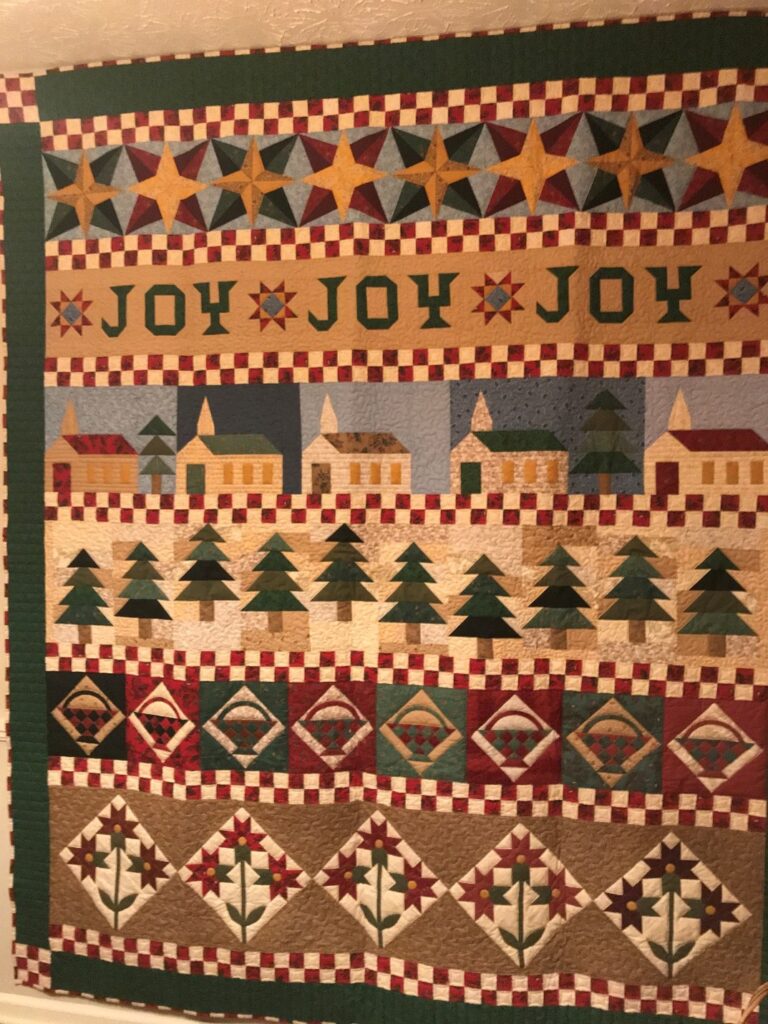

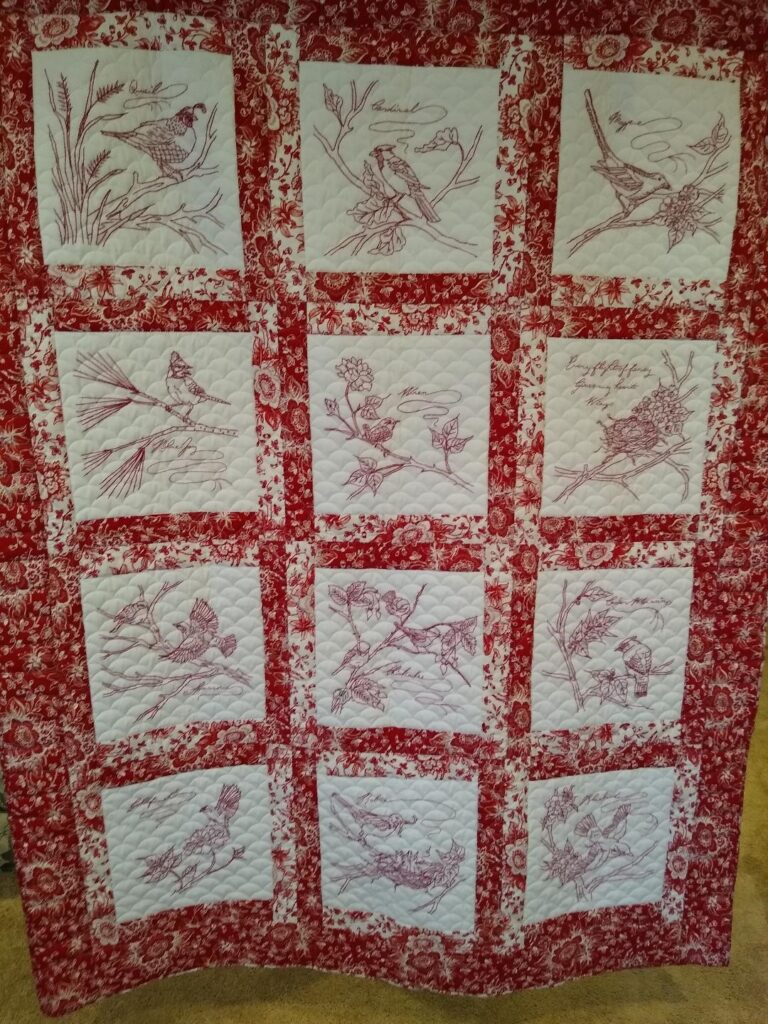

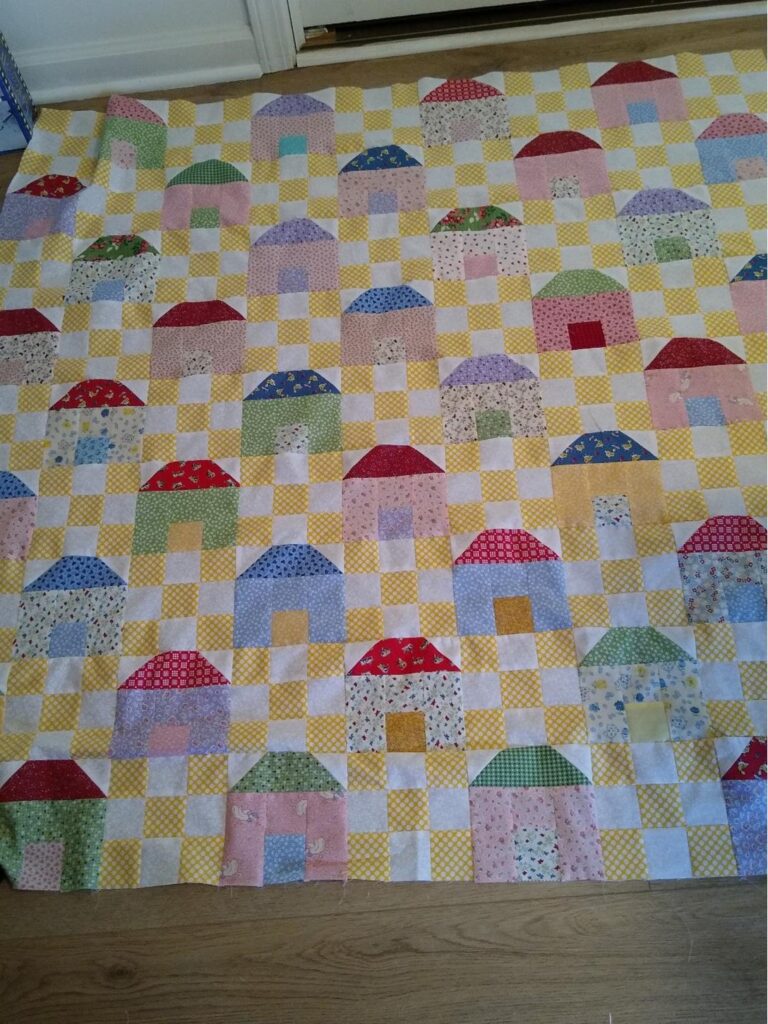

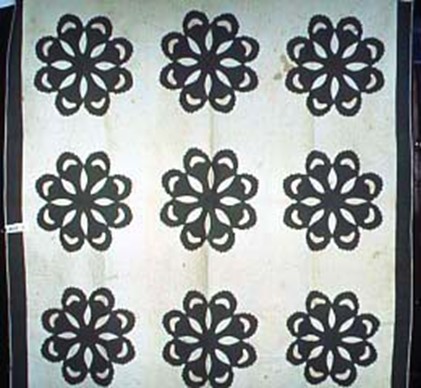

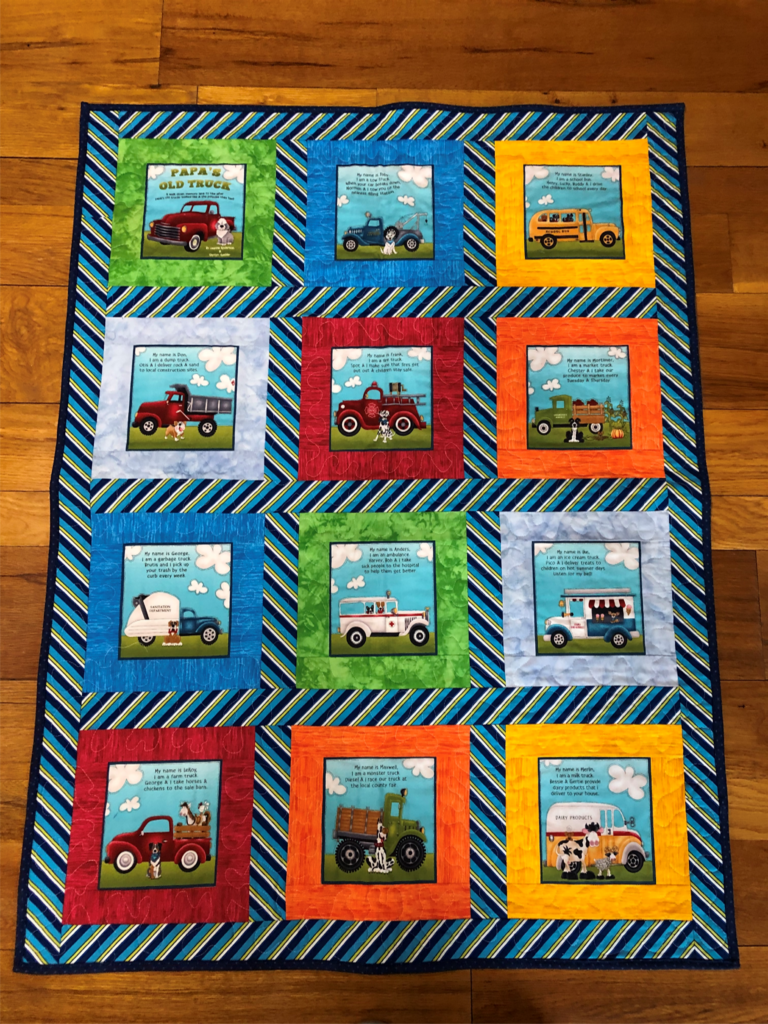

PS. Here are my two “Porcella” quilts; one with bright colors and checkerboard and the other with a nature inspiration. Both have my hand dyed fabrics. If you have any to show, post photos when the blog comes out on The Quilters Hall of Fame Facebook page.

Suggested Reading:

SAQA interview. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_T8ayK9Um-k

Bio information. https://quiltershalloffame.net/yvonne-porcella/

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco clothing. https://art.famsf.org/search?search_api_views_fulltext=Porcella

Halloween Quilt. https://quiltershalloffame.pastperfectonline.com/webobject/BC0F976D-9D99-45E7-A15B-915008567929

Yvonne’s blog. http://yvonneporcella.blogspot.com/

Alliance for American Quilts. https://web.archive.org/web/20100804004036/http://www.allianceforamericanquilts.org/treasures/main.php?id=10

Pinterest images. https://www.pinterest.com/robinson6702/yvonne-porcella/

Olive Stuffing. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OGwsRz842TE

Los Angeles County Museum of Art. https://collections.lacma.org/search/site/Porcella?f[0]=bm_field_has_image%3Atrue