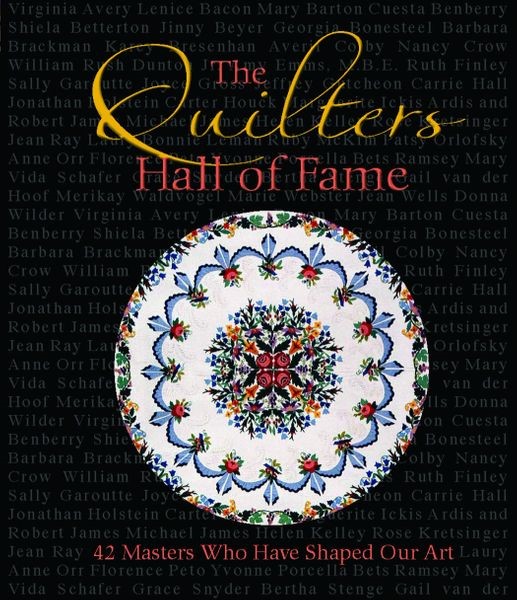

Carrie Hall: Co-author of “The Romance of the Patchwork Quilt in America”

As I do my background reading to write these posts, I usually find myself wishing I could meet the Honoree. These women and men are always remarkable, and there’s often some twist that makes them real for me. But that isn’t the case with this week’s subject, Carrie Hall; I had a hard time warming up to her. But read on, and maybe we’ll find something interesting.

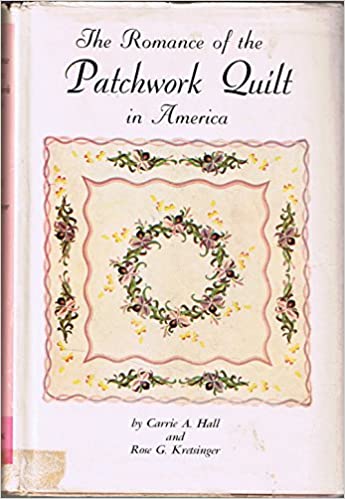

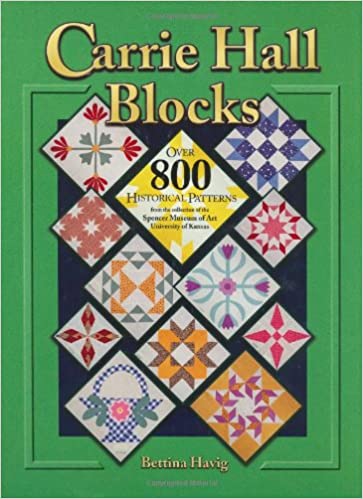

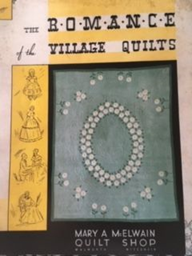

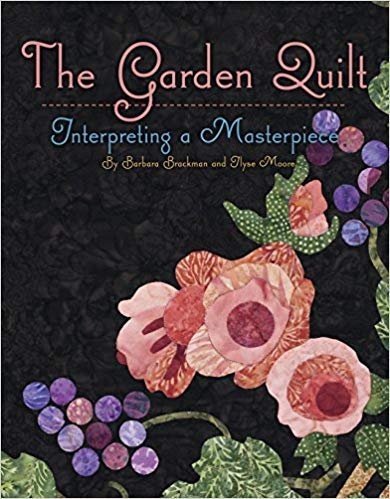

Let’s start with the quilt stuff. Carrie Hall lives on today on eBay, Amazon, AbeBooks and other sites through two things: the book she wrote with Hall of Fame Honoree, Rose Kretsinger, titled The Romance of the Patchwork Quilt in America and for Bettina Havig’s book titled Carrie Hall Blocks.

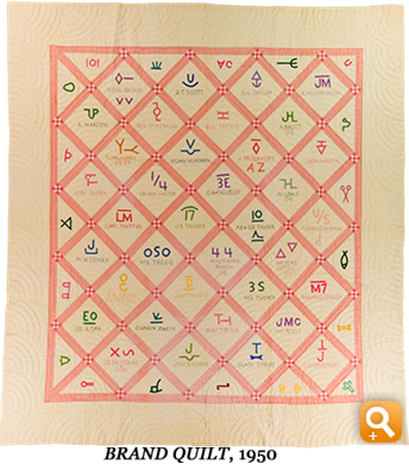

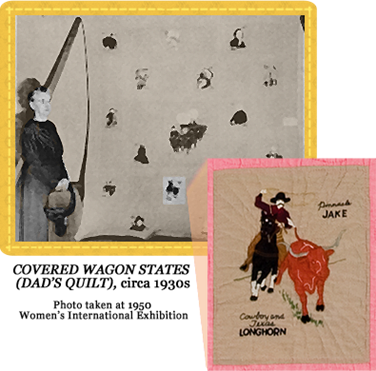

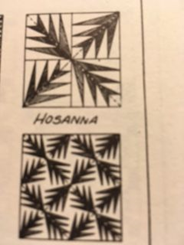

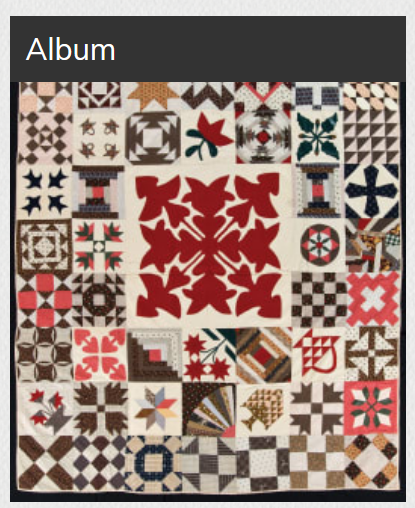

Both books include photos of the hundreds of quilt blocks made by Hall between 1900 -1935. She, like Hall of Fame Honoree Mary Barton discussed in an earlier blog, went on the lecture circuit during the “Colonial Revival” of quilting, and used actual blocks to punctuate her talk. Here’s Carrie dressed for a performance/ lecture, followed by a few of her blocks with the names she gave them; if you look at all of them on the site below, you’ll find that you may call some of the blocks by different names. In some cases, Hall was a stickler for historical accuracy, but in others, she didn’t mind being creative or redundant. Makes me wonder what she said in those lectures, but I shouldn’t be too critical because glamorizing the past was a shortcoming of many early quilt history efforts.

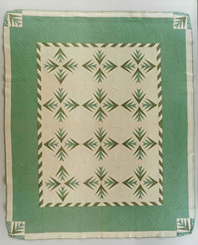

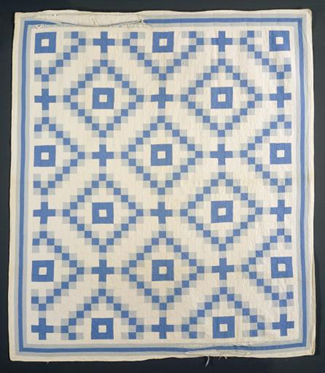

I like to call the one on the left “Going to Chicago” (that’s where I’m from), and you may know it by one of its several other names. Hall used the first recorded name from an 1884 publication—probably what she grew up with. Names are funny; the same source that named “New Four Patch” called it “World’s Fair” when they put it out again 55 years after the original.

She lived in Leavenworth Kansas while she was making these blocks, so maybe that accounts for the one on the left. She is the only source cited by Brackman (Encyclopedia of Pieced Quilt Patterns) to give a name to this pattern, and I guess she wanted to honor her home town. As I said, sometimes she’s historically accurate, and sometimes she’s creative.

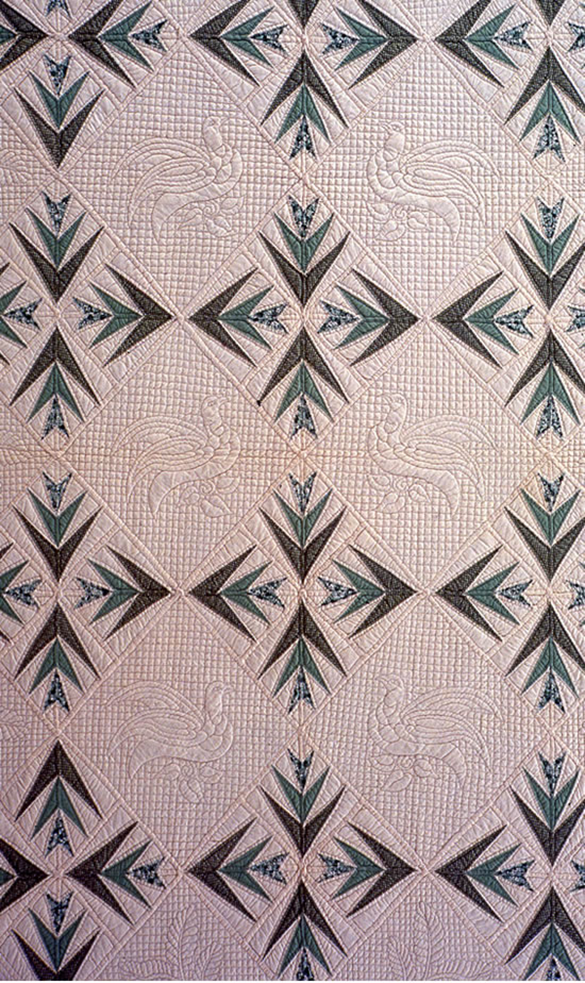

And look; here are two very different blocks with the same name, and there are at least two other blocks also named “Rose of Sharon” in the Hall block collection:

-

Rose of Sharon -

Rose of Sharon

Not only was Hall inconsistent and repetitive in naming, but she took great license with botany as well. I’m not talking about the stylized, pieced, modern pansies, etc; no one expects those to be accurate. But look at these two versions of the same plant:

-

Poinsettia Quilt Block -

Poinsettia Quilt Block

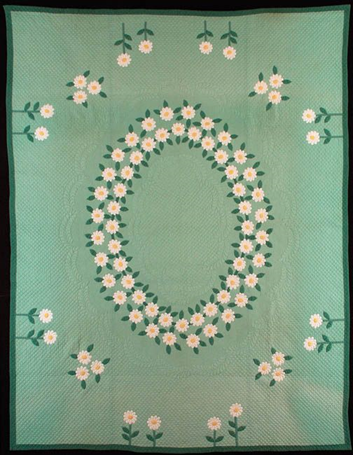

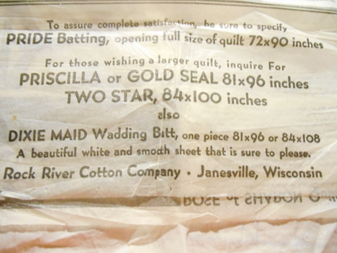

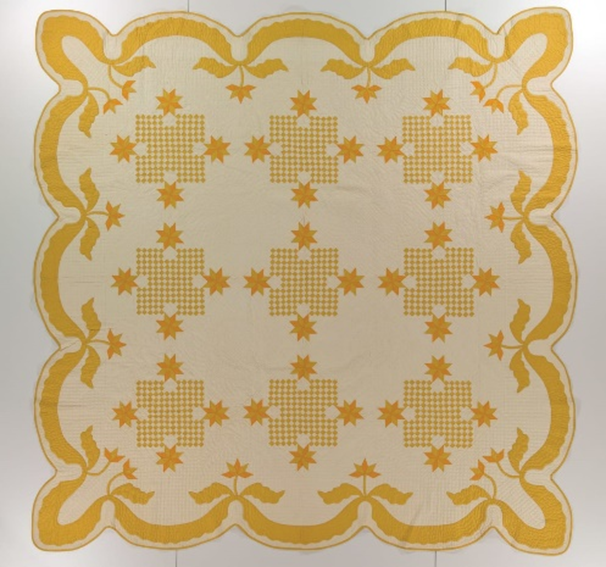

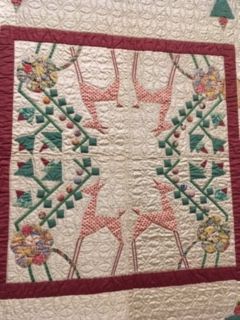

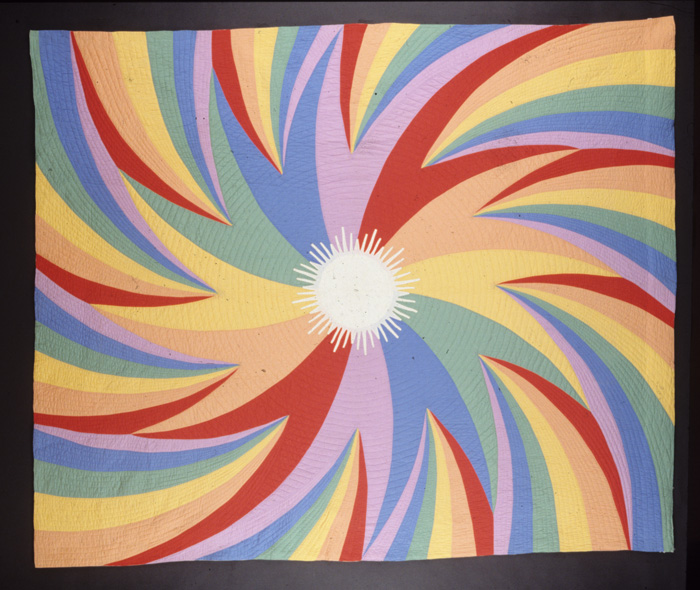

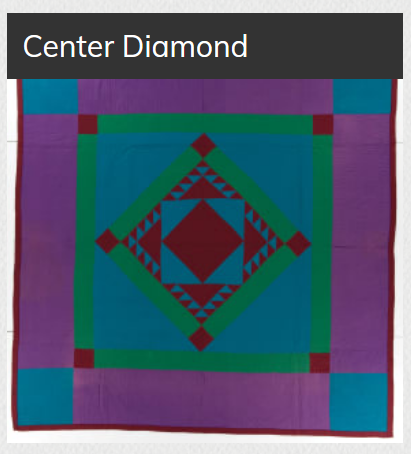

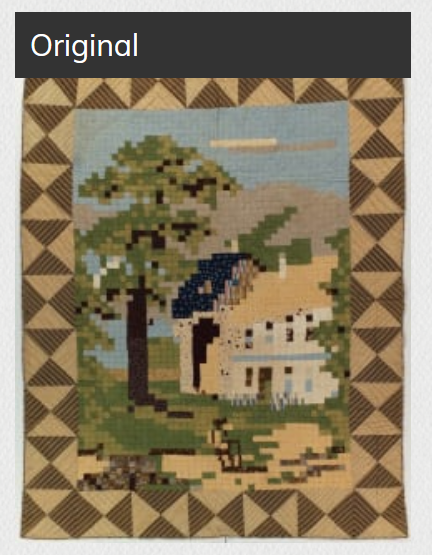

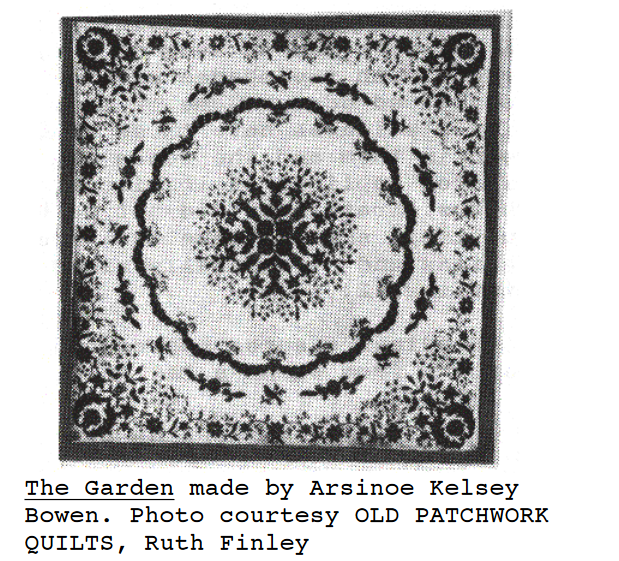

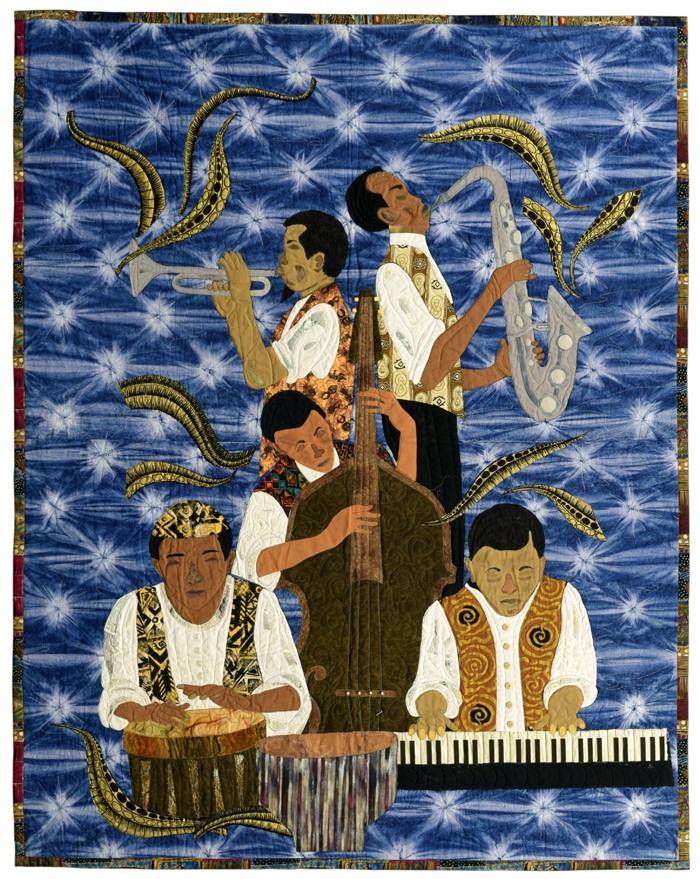

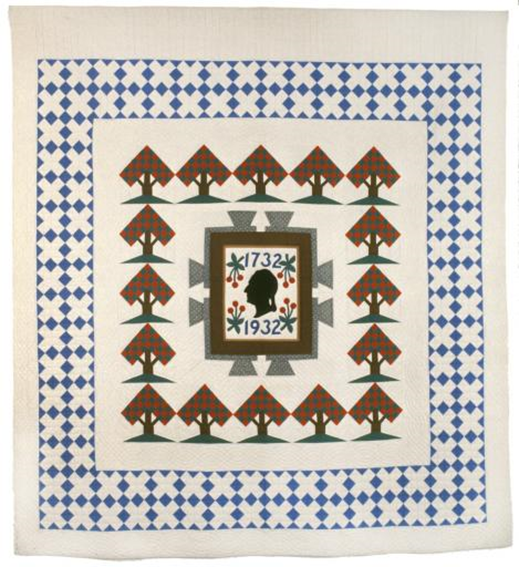

Am I getting a little waspish? Sorry; I told you I couldn’t warm up to her. But I really do admire Hall’s work; some of the designs require more sewing skill than I can muster (I sure wasn’t piecing LeMoyne stars at age seven and winning first place at the county fair at age 15), and I can’t imagine making that many blocks. With over 800 of them (1,057 by Brackman’s count), varying from 8 inch pieced blocks to 16 inch applique blocks, she could have made over a dozen quilts! Wait, she did make quilts—many for charity, and probably few, if any, for the contests that captivated her contemporaries. Here are two examples:

I love this one for its blue and white border and for the red in the trees to represent cherries, and the axes masquerading as a frame. I love the next one because it’s all blue/white and reminds me of the old ceramic tile patterns that used to be in the entries of 1930s drug stores and five-and-dimes (and old bathrooms).

The block and quilt images are all taken from the website of the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas. You can see more of the items donated by Carrie Hall at the link below. Be warned: there are 92 pages and many of the blocks have no image available, but starting at about page 87, you’ll find quilts and clothing made by her co-author, Rose Kretsinger which are worth seeing too.

Well, that’s the quilting aspect of Carrie Hall’s entre’ to the Hall of Fame. She had another interesting career in the world of fashion. And really, aren’t fashion and quilt fabrics related? That’s the topic of another post, but let’s see how Hall segued from one to the other and back again.

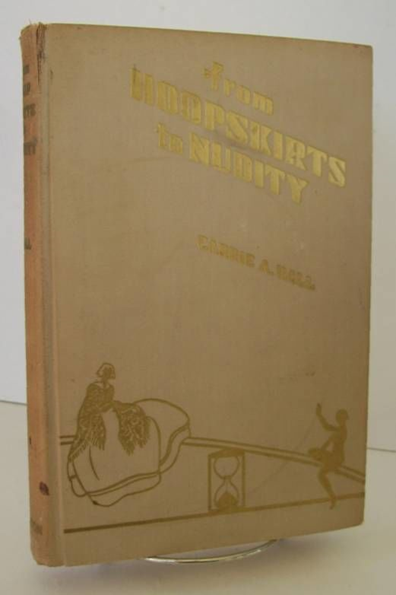

After a stint as a teacher (how many of us were teachers? I had 7th and 8th grade for science, religion and art—what a combo!) and later as superintendent, Hall turned to dressmaking. Under the title “Madam Hall, modiste”, she developed a thriving couture business catering to local society ladies, and included General MacArthur’s mother among her clientele. In 1938, she wrote a book I think should be required reading in all college fashion design programs: From Hoopskirts to Nudity, calling it “A review of the follies and foibles of fashion, 1836-1936”. The cover of the 1946 edition even emphasizes the silliness of her topic, showing two “fashion” figures on the teeter-totter of time.

Having been in the fashion business, Madam Hall knew whereof she wrote. She gives detailed descriptions of designs and construction techniques, along with plenty of information about accessories. But throughout, she expresses an amused, almost disdainful attitude toward fashion. She encourages her readers to develop their own style, to wear what is becoming to their own figure, and to choose what is most compatible with their own personalities. She knows how fickle fashion can be!

Her writing is at times chatty, at times moralistic, and always peppered with literary references. You won’t be surprised to learn that Shakespeare had a lot to say about dress, but would you have thought she could work in quotes from Confucius and the ancient Greeks? Within two pages, she cites Ben Johnson, Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Carlyle. There’s also lots of doggerel too, just to keep it from getting too high brow. And in case you are wondering about the title, it’s appropriate: she not only reviews the “Flora Mc Flimsey” modes of the 1920s, she goes so far as to include a photo of a nudist colony. Daring! (And I’m not gonna cut and paste that; find it yourself.)

The ups and downs of fashion that she wrote about turned personal for Carrie Hall. A combination of the ready-to-wear market and the Depression saw the end of her couture establishment. She re-invented herself in quilting, but that didn’t last either, as travelling for lectures became difficult and her finances declined. But Hall was a survivor; she had “braved it all” (grasshoppers, crop failures and more) as a child of Kansas homesteaders in the early 1870s, and the difficulties of her later life weren’t going to keep her down. Her final career was as a doll maker.

These weren’t common playthings. Here are some excerpts from an article in the Kansas City Star, May 39, 1948 that record the subject-matter variety and detailed construction of the Hall dolls.

Also mentioned in the article were 50 dolls representing biblical figures (now in the collection of Nebraska Wesleyan University) and dolls made to order from old photographs.

Hall’s dolls are sought after by collectors today, and she’s occasionally written up in the antique doll magazines. I’m not into dolls myself, but I couldn’t resist purchasing a five-page article about Hall’s fashion dolls on eBay. It should arrive in time for an update in next week’s blog. Below are some of her items sold on the RubyLane website. Look at the fabulous detail and remember that these are not full or even half size—they’re doll clothes.

Well, I think Carrie Hall has turned out to be more interesting than I first found her. And definitely more admirable. I’m glad I kept digging and was able to introduce myself and you to this skilled, creative, whimsical, resourceful Honoree.

Your quilting friend,

Anna

Bio info https://quiltershalloffame.net/carrie-hall/

Blocks at Spencer Museum https://spencerartapps.ku.edu/collection-search#/search/works/Carrie%20A.%20Hall