It’s the best of times and the worst of times to write about Honoree Cuesta Benberry. The best because February is Black History month and Cuesta was one of the first Black quilt historians; the worst because, as she reminds us, Black quilters are “always there” and so it’s artificial (or wrong, or just plain sad) to focus the discussion on a single month. And, with Cuesta Benberry, about whom so much has been written, I could easily spill over into March, or even April, but I’ll try to focus. You can get an overview of her story at the bio link below.

In case you don’t recognize the “always there” reference, the source is Cuesta’s book, Always There: The African-American Presence in American Quilts. If you want a peek inside this book, go to the “gallery” link below. She also wrote A Piece of My Soul: Quilts by Black Arkansans. (See the link below for an interactive video about the quilters and quilts in this book.)

I said that a lot has been written about Cuesta Benberry, but it’s also true that she herself wrote a lot. In addition to regular contributions to quilting magazines such as Nimble Needle Treasures, Quilters’ Newsletter and The Women of Color Quilters’ Network Newsletter, she wrote scholarly papers about her research. In 1980, her first such paper, “Afro-American Women and Quilts,” was published in Uncoverings, the journal of the American Quilt Study Group. There she laid out what would be her two-fold focus as a quilt historian studying Afro- American quilts:

I am investigating the role of quilts, in a historical context, in the lives of black Americans. This means quilts made by black women, and quilts not made by black women, but which have a relationship to their lives. Why did I include quilts made by white women in my “ Afro-American Women and Quilts” project? A study of these quilts portray(s), in a very vivid manner, the concepts of a large segment of white Americans about black Americans at various points in American history….

For the most part, the university scholars have concentrated their studies on a specific type of Afro-American quilt. This is a quilt with an African heritage design—an ethnic quilt…. An historical approach requires me to scrutinize all types of quilts made by black women, including the Euro-American traditional quilt.

Here’s a list of the extensive scholarly writings which followed that first Uncoverings paper:

- “White Perceptions of Blacks in Quilts and Related Media,” Uncoverings, 1983

- “Quilt Cottage Industries: A Chronology,” Uncoverings, 1986

- “The Nationalization of Pennsylvania-Dutch Quilt Patterns in the 1940s to 1960s,” Bits and Pieces: Textile Traditions. Ed. Jeannette Lasansky, Lewisburg, PA: Oral Traditions Project, 1991. p. 80-89.

- “Afro-American Slave Quilts and the British Connection,” America in Britain, American Museum in Britain, Claverton Manor (Bath, England). Vol. XXV, Nos. 2 and 3 (1987).

- “Marie Webster: Indiana’s Gift to Quilts,” Chapter four in Quilts of Indiana: Crossroads of Memories. Goldman, Marilyn and Marguerite Wiebusch, et al. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. 1991.

- “Quilt Cottage Industries: A Chronicle,” Quiltmaking in America: Beyond the Myths. ed. Laurel Horton. Nashville, TN: Rutledge Hill Press, 1994. p. 142-155.

- “African American Quilts: Paradigms of Diversity,” International Review of African American Art. Hampton University Museum. Hampton, VA. Vol 12 No. 3. Winter 1995.

- “The Threads of African American Quilters are Woven Into History,” African American Quiltmaking in Michigan. MacDowell, Marsha, ed. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press in collaboration with the Michigan State University Museum. 1997.

Cuesta’s work was nothing, if not comprehensive. If you want to get a quick “visual” of how extensive her writings and collections are, check out the short video about unpacking the donation of her legacy to Michigan State University. All those boxes! She also gave her collection of pattern blocks to the Quilters Hall of Fame, and you can get a little taste of them at the link below.

Cuesta herself wasn’t a quilter, but she did participate in Round Robin exchanges with other quilt pattern historians, including our Honorees, Mary Schafer and Barbara Brackman. The one quilt she did make provides a visual study of her research results; it’s a sampler of blocks made by or, or related to Afro-American quilters. Here’s the quilt:

You can hear Cuesta’s own words about the quilt at the Quilt Alliance link below, but I’ll give you my thoughts too. (The blocks are identified by rows across (ABC) and numbers down (1-2-3-4).

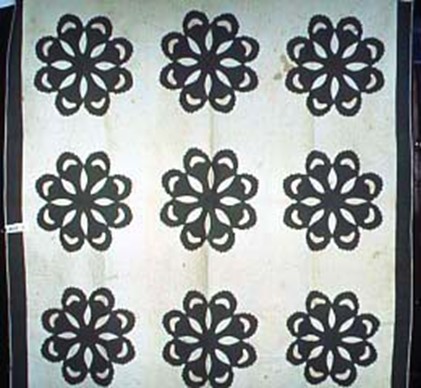

Block A-1 is an unnamed pieced block made around 1920 by an Arkansas woman. It appears to be based on the Maltese Cross group, but I can’t find it in Brackman’s Encyclopedia of Pieced Quilt Patterns; there’s nothing like it with the small square center. I wonder if Cuesta included this one as a testament to the precision skills of some Black quilters? So often, these skills were overshadowed by the simple designs and “improvisational” patterns that are associated with what she called “ethnic” quilts.

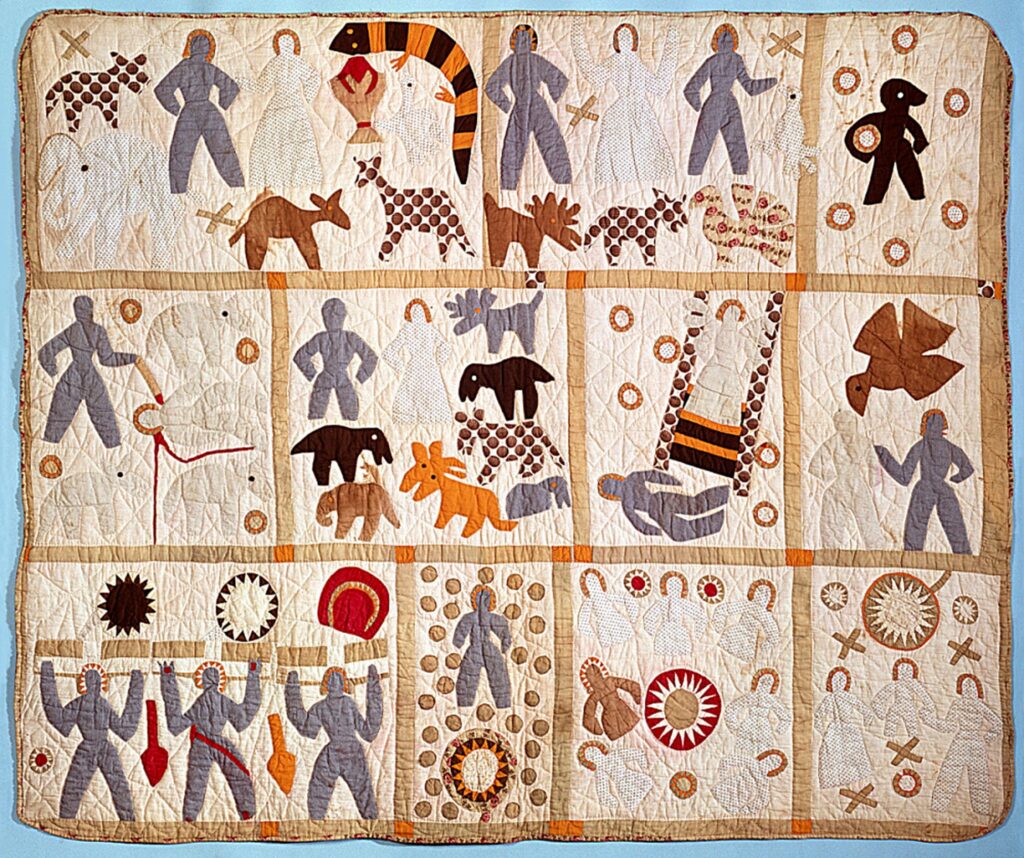

Block B-1 will be recognized by many as a scene from the Harriet Powers Bible quilt. In the interest of providing “eye candy”, here’s the original quilt. I love the fact that this work, with its simple motifs, was a contemporary of over-the-top crazy quilts.

Bible Quilt. C. 1890. Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_556462

Block C-3 is described by Cuesta as an unnamed applique block based on a quilt made by “slave labor” for the Abernathy family in 1850 near Gastonia, South Carolina. I went down the research rabbit hole and found a Gastonia, North Carolina with an Abernathy family (the home place is now an equestrian center, which really sidetracked me); but could it be the same family? Then I found this “Carolina Medallion”:

It was made in Abbeville, now McCormick, South Carolina, which isn’t near Gastonia. There are four other quilts of this pattern and time period in the South Carolina documentation project. Which one, if any, was Cuesta’s inspiration? I’m sure if I had access to her notes, they would tell me. But in the meantime, it raises the question of how this pattern was spread—a study for another day.

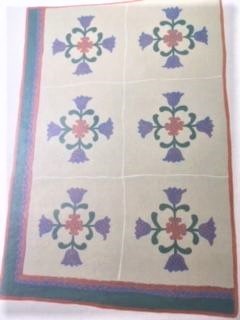

Before I read about block A-2, I thought that maybe it had been included as an example of paper or simple piecing to show that Afro-American women did more that “ethnic” quilts. Then I learned that this is a pattern called “May Apple” taken from a quilt made in the mid-1960s by the Freedom Quilting Bee of Gee’s Bend, Alabama. Most of us now associate Gee’s Bend with a particular style of quilt, but in the beginning, there was just a group getting together to socialize. “They were doing Wedding Rings and May Apples and all sorts of designs.” [The Freedom Quilting Bee: Folk Art and the Civil Rights Movement. Nancy Callahan Univ. of Alabama Press.]

That gradually changed as the group moved to marketing, commercial success and wide-spread popularity, but the May Apple block remains a good reminder of the early days. And it bears out Cuesta’s premise that Afro-American quilters don’t just make what we now think of as Gee’s Bend quilts. Cuesta called block B-2 the most important one on the quilt. It is taken from a small quilt made in Boston for an 1836 anti-slavery fund-raising fair. An inscription on the original carries part of a poignant poem which I’ve included below the photo of the original quilt. In a letter to a friend, Child reports the success of the fair and that her quilt raised $5.00 for the cause.

Mother! when around your child

You clasp your arms in love,

And when with grateful joy you raise

Your eyes to God above,

Think of the negro mother, when

Her child is torn away,

Sold for a little slave, — oh then

For the poor mother pray!

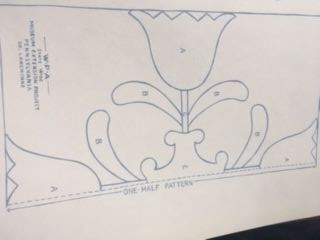

Next comes the WPA Tulip in block C-2. Here’s the original.

This doesn’t look like the reproduction I have of a WPA pattern, and nothing in Brackman’s Encyclopedia of Applique has such a rounded center piece. Here, with a shout out to Barb Garrett and her group that spearheaded the reproduction work, is what I know as the WPA Tulip pattern.

But Cuesta has a great story in the Quilt Alliance interview, and the original quilt was made by Minnie Benberry (presumably a relative), so I think this is a case where we’ll have to accept the oral history as adding to, rather than contradicting, what we think we know.

Block A-3 is Buzzard’s Roost copied from a “slave cabin quilt”. Cuesta’s adaptation has as the center quilting design what some call an eagle, but which she says is an authentic African design representing a buzzard. Cuesta did a lot of study and research into such designs, so I’ll take her word for it.

Block B-3 is an original applique design seen on a circa 1870 Kentucky quilt. Cuesta calls it “Parasol Vine”, and it’s reminiscent of the floral clusters seen on Baltimore Album quilts.

I recognized block C-3 right away (Robbing Peter to Pay Paul; it’s the dust cover of Honoree Florence Peto’s book Historic Quilts). What I learned from Cuesta’s inclusion of this block was that Peto found it noteworthy because the maker, Sarah Harris, was allowed to put her name and date on the quilt. Such attribution was unusual for slave work in 1848.

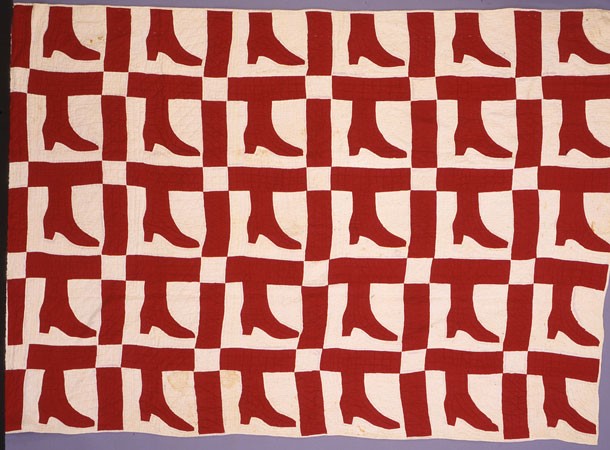

The Lady’s Shoe block In A-4 comes from a 1890’s family quilt and was owned by Cuesta. It’s the only block in which she didn’t replicate the original construction method; the original was pieced, but Cuesta appliqued the block. Can anyone tell me why someone thought to use this particular image in a quilt? It’s tempting to read some metaphorical meaning into it—and the 1890s were certainly ripe for commentary—but maybe the quiltmaker just liked the idea of a graphic image. (It worked for Warhol and his soup cans over a half century later, so why not?) Here’s the original quilt.

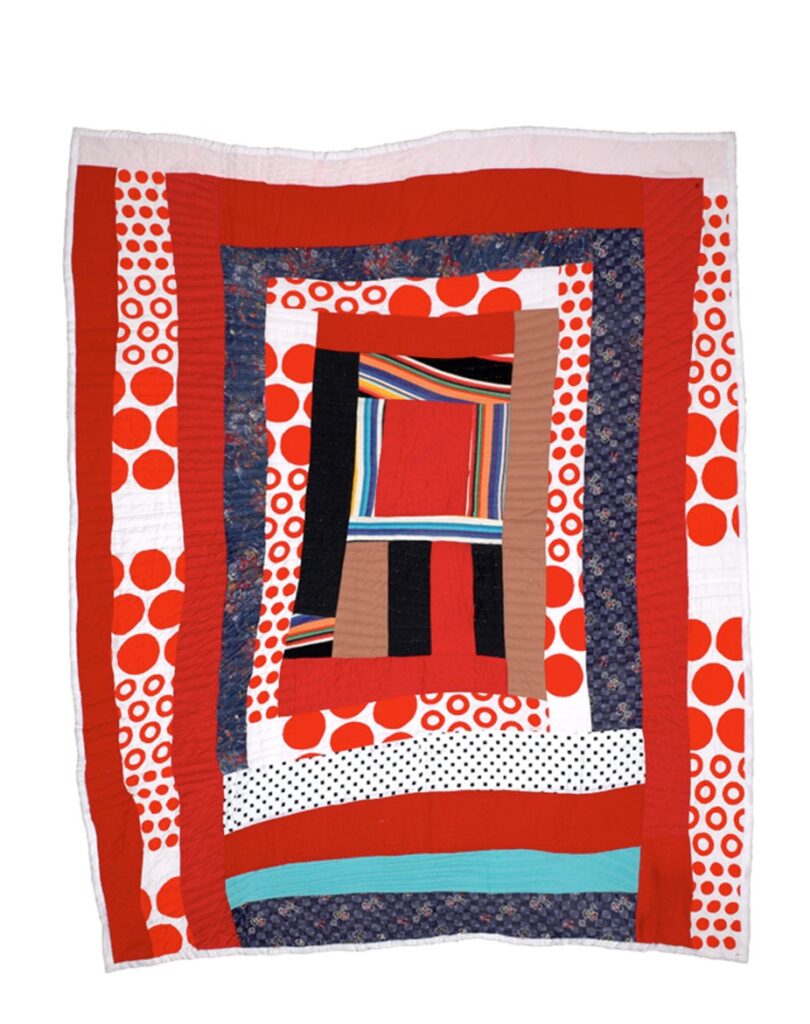

At last, with block B-4, we come to the strippy style that is now so associated with Afro-American quilts. The inspiration for this was a 1980s quilt. Cuesta explains that the narrow looms used in West Africa dictated that narrow strips be sewn together. This necessity led to designs called “Housetop”, “Lazy Gal”, and “Brick Wall” among others. Here are a couple of examples made by two of the prominent Gee’s Bend quilters.

Housetop Variation by Loretta Pettway

Housetop Variation by Mary Lee Dendolph

Both: Photos by Steve Pitkin/Pitkin Studio courtesy of Souls Grown Deep Foundation for https://www.arts.gov/stories/blog/2015/quilts-gees-bend-slideshow

And finally, Block C-4 is a Mammy applique from a mid-20th century Illinois quilt. In her original Uncoverings paper, Cuesta wrote about how the stereotypical and often derogatory impressions of blacks by whites showed up in “Mammy” quilts. This one, however, doesn’t reflect any of that negativity, but instead gives the figure a mainstream profile (think Sunbonnet Sue with a wrapped head).

To sum up, this quilt is Cuesta Benberry’s research philosophy in stitches. It has historical accuracy backed by documentation (which I’d like to get my hands on some day), puts quiltmakers in historical context (whether it’s 1930s WPA designs or a pattern from the 1850s), and explores all styles of quilts.

Cuesta inspired and encouraged many quilt historians. At her induction to the Quilters Hall of Fame, she said

Quilt researchers, we of the quilt community, believe what you are doing is vital. Due to the works of early investigators, you of the present generation of researchers, have a basis of quilt knowledge from which to work. Now go forth and build on that basis, explore undeveloped concepts and investigate old and new ideas. We, the quilt community, charge you with the task of building a body of quilt information whose veracity and scholarship will be respected by all.

She certainly set a good example for us all. Respect to you, Cuesta Benberry!

Your quilting friend,

Anna

PS. Many readers will have personally known Cuesta and may have even talked with her about her choices of blocks. If you have more information about the original quilts that inspired Cuesta’s blocks, please comment. I’d appreciate your insight.

Bio information. https://quiltershalloffame.net/cuesta-benberry/

Always There gallery. https://web.archive.org/web/20100805045357/http://www.allianceforamericanquilts.org/treasures/photos.php?id=4&galleryid=6

Piece of My Soul video. https://web.archive.org/web/20071107075405/http://www.oldstatehouse.com/piece-of-my-soul/

Unpacking video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SXA9r2MzbXQ

I’m Anna Harkins, and I volunteer on the Collections Committee at The Quilters Hall of Fame. What else would you like to know about me? Married, no kids; one old horse, retired, and live in a western suburb of Chicago. I’ve been quilting for about 20 years (I wish I could say I learned from my grandmother, but some of us come to this later than others), and I’m a quilt history dilettante, “a person who cultivates an area of interest, such as the arts, without real commitment or knowledge.” There are real scholars among you, and I have no pretensions to that level—hats off to you! But I am interested, especially in the people who have made up the quilt world here in the US, which is why I’ve agreed to blog for The Quilters Hall of Fame. I plan to write every week, and I hope you’ll join the discussions.